The healthcare industry has been leveraging smartphone technology for years, from monitoring disease symptoms to curbing the opioid crisis, often through mobile applications. But now, a research team from the University of Michigan Kellogg Eye Center has modified a smartphone’s camera to help detect the most common form of diabetes-related eye disease.

Currently, diabetic retinopathy is diagnosed by an ophthalmologist who analyzes a retinal image taken by a retinal camera. Not only does this process require expensive equipment and special training, but it can also take nearly a week for the ophthalmologist to interpret the images and decide if a patient has diabetic retinopathy. If caught too late, patients can go blind from the disease.

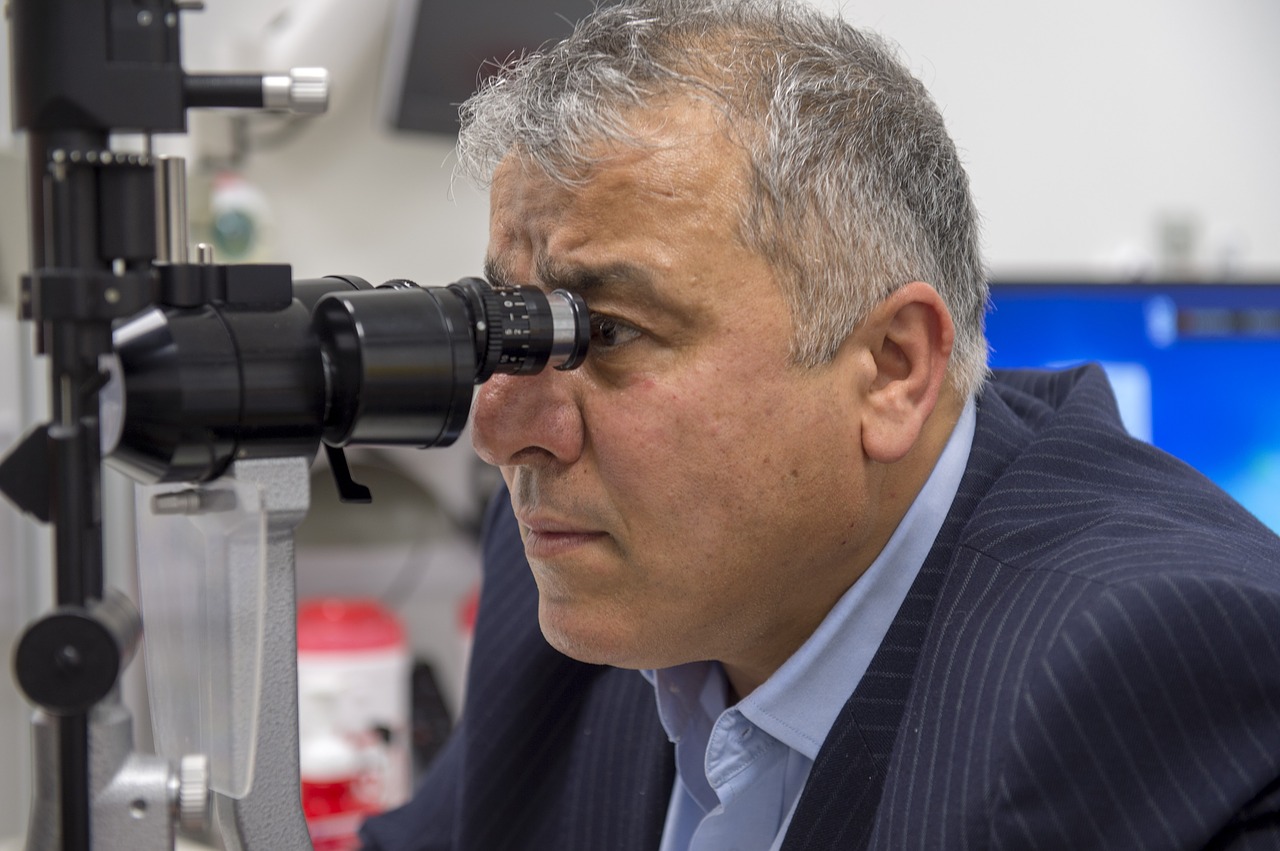

“To make screening truly accessible, we need to provide on-the-spot feedback, taking the photo and interpreting it while the patient is there to schedule an eye appointment if necessary,” said Dr. Yannis Paulus, a Kellogg vitreoretinal surgeon, in a news release.

Dr. Paulus and his team combined RetinaScope, a device designed in-house that turns a smartphone into a retina camera, with EyeArt, an artificial intelligence (AI) platform developed by Eyenuk, into a diagnostic device that takes a retinal image, analyzes it, then informs the operator if the patient should be referred to an ophthalmologist for follow-up.

The team tested the device for its ability to tell if someone has diabetic retinopathy (sensitivity) and its ability to tell if someone does not have diabetic retinopathy (specificity). To determine if the test was accurate, they compared the device results with a gold standard technique and also brought in two independent experts to examine the device-captured retinal images.

Based on a study of 69 adults with diabetes, the device scored 86.8 percent on sensitivity and 73.3 percent specificity. Not only is this level of sensitivity greater than the recommended minimum for an ophthalmic screening device, but it’s close to what was achieved by a similar device developed by biotech company, IDx, which was cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) last year. Unlike Dr. Paulus’ device, IDx-DR uses a fundus camera that’s specifically designed to photograph the retina rather than modifying the camera of a smartphone.

“This is the first study to combine the imaging technology with automated real-time interpretation and compare it to gold standard dilated eye examination,” said Dr. Paulus. “And the results are very encouraging.”

The results of the study were presented at the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology annual meeting. Dr. Paulus says his team is working on improvements to both the hardware and software components of the diagnostic in pursuit of FDA approval.

The researchers hope that the convenience of their device will encourage more patients to get screened for diabetic retinopathy. Given that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) predicts that 16 million people will be living with diabetic retinopathy by 2050, the need for more reliable screening tools has never been greater.

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN