How can pharma companies improve their chances of getting their drug approved? According to a new PLOS Genetics study, the key is to develop a drug that targets a specific gene linked to a disease.

“The findings from this study demonstrate that human genetics evidence is predictive of historical drug development success,” said lead author Emily King, a postdoctoral fellow at AbbVie.

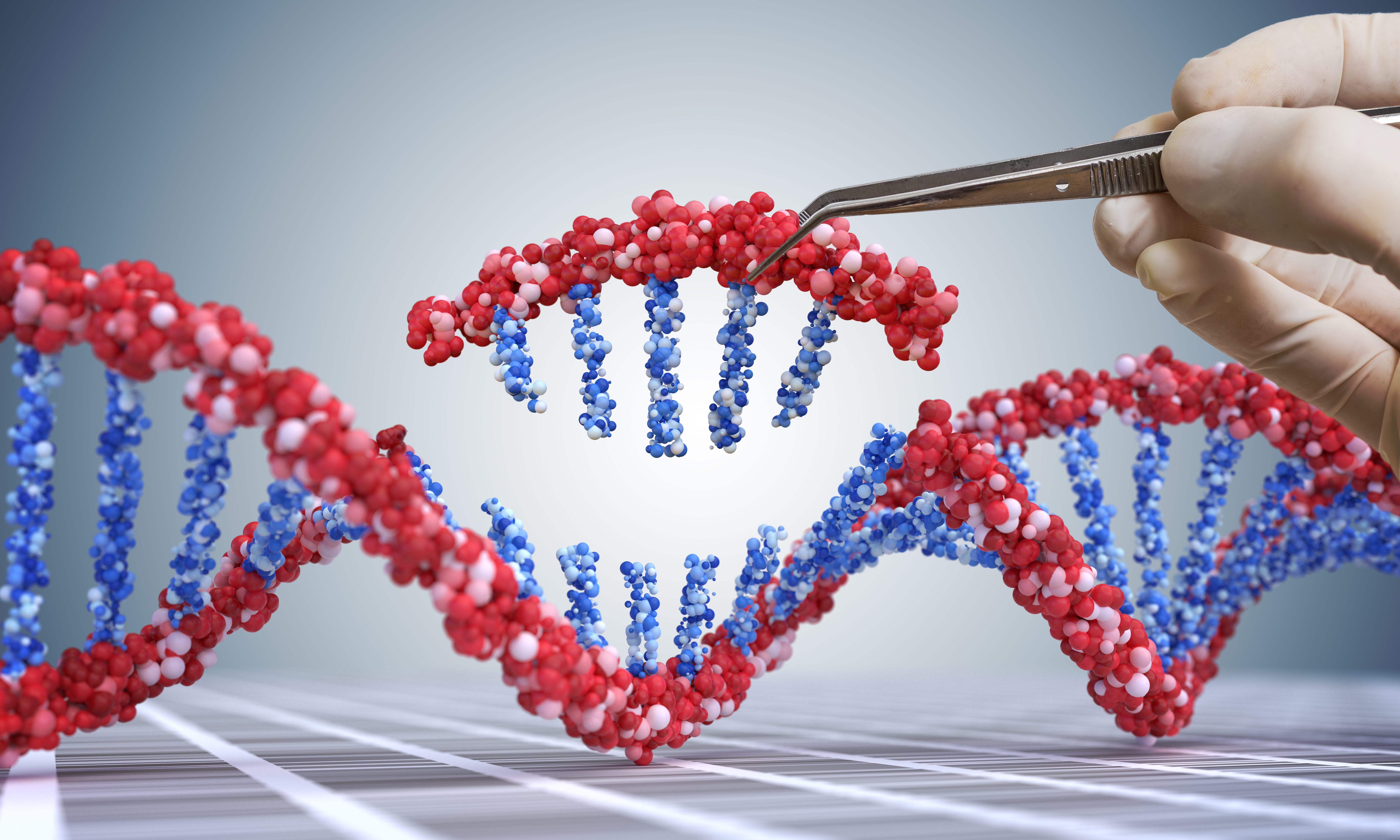

Genetic evidence, as defined by the study authors, refers to an association between a gene target and a trait sufficiently similar to an indication. The authors found that genetic evidence was a strong predictor of later drug approval.

These findings corroborate a 2015 study where another group of researchers found that approvals were twice as likely if drugs were correlated with genes in this manner. For pharma companies, this could mean a significant payoff for their R&D efforts, which could cost between $3 million to $10 million.

“Human genetics has the potential to help us to focus our investment on drug programs that are most likely to have an impact on patients,” said Howard Jacob, vice president and head of genomic research at AbbVie. “Studies like this one further demonstrate the importance of human disease genetics in drug development.”

Moreover, the researchers found that drugs were less likely to be approved if there was a genetic association between the target and a different indication. That is, the drug may have had off-target or negative side effects that would lead to an early stop in clinical development, the researchers wrote.

It may seem obvious for a pharma company to develop drugs based on genetic information, given how much scientists have learned from advanced genetic sequencing. But without validation, scientists remain uncertain about the biological mechanisms that connect specific gene variations with a particular disease.

Even with an undisputable gene target-indication pairing, the chances of a successful approval are still not guaranteed. The candidate drug is still expected to demonstrate some level of safety and efficacy, and sponsors are responsible for ensuring regulatory submissions are complete and accurate.

The high cost of drug development coupled with the relatively low approval rate (about five to 10 percent) puts pressure on pharma companies to deliver. This new study, which draws numbers from a larger dataset, could help drug makers decide on the next development program that is most likely to succeed.

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN