Some drugs granted breakthrough therapy designation by the FDA may not be backed up by sufficient evidence of efficacy, according to a recent study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. While the status was introduced in 2012 in an attempt to accelerate the approval process for new therapies that appear to beat the standard-of-care treatment in smaller trials, some believe it could be doing more harm than good.

“These drugs are being accelerated through development, and as this study shows, they are being tested on the basis of far less rigorous studies — studies that have substantial limitations to them in terms of their scientific rigor,” Aaron Kesselheim, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, told The Washington Post. While Kesselheim wasn’t one of the researchers involved in the current study, he does maintain that the term “breakthrough” is misleading and should be changed to a word that’s less loaded with promise.

Between 2012 and 2017, 46 drugs have been granted breakthrough therapy designation by the FDA, with the number of new drugs given this status steadily increasing almost every year except in 2016. For example, in 2016, seven therapeutics were granted the status, compared to 17 the following year.

In the current study, the Yale School of Medicine researchers found that 40 percent of pivotal trials used to approve these breakthrough therapies used a randomized design – one of the measures used to prevent bias in studies whereby patients are randomly assigned to receive the active drug or a placebo. Blinding of both patients and doctors another tool to reduce bias, however in about half of the pivotal trials included in the analysis, physicians or patients were aware of whether they were being given the drug in a type of trial known as an open-label study.

What’s more, almost half of these studies did not include a placebo arm with which to measure the efficacy of the new therapy. Placebo-controlled trials are also a hallmark of clinical research, and without a control group, it can be hard to determine whether the drug is actually working.

“If we are going to be making this trade-off to allow novel drugs to come to market on the basis of evidence that is generally accompanied by greater uncertainty, we must be committed as a clinical and scientific community to ensuring that high-quality, rigorous post-market trials are conducted within a reasonable period,” said Dr. Joseph Ross, associate professor of medicine at Yale, and senior author on the study.

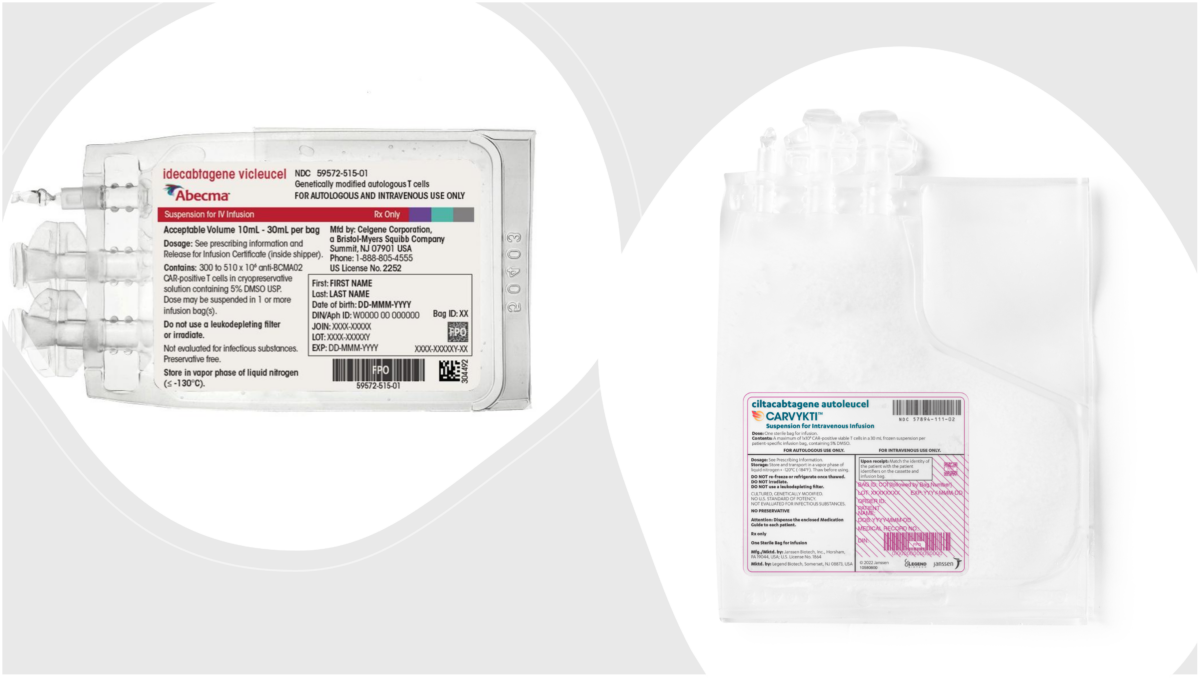

However, according to Janet Woodcock, FDA’s director of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, certain clinical trial designs are more suited to some therapies and many of these studies produced strong evidence to support their breakthrough designation. Some more targeted drugs – such as immunotherapies designed to treat a small subset of cancer patients – may be more difficult to fit within the traditional trials framework, which requires that investigators explore alternate study designs. For example, smaller patient populations and disease areas in which patients are terminal and unlikely to live if assigned to receive the placebo are just some of the challenges that rule out a traditional trial.

“This is probably the trajectory of drug development, as the science advances so much,” said Woodcock. “What has been traditional drug development is changing, and I know that’s causing discomfort, but we’re very confident the drugs out there are making tremendous” benefit for patients.

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN