Every year, the European Organisation for Rare Diseases (EURORDIS) organizes Rare Disease Day to raise awareness of the over 6,000 identified rare diseases that affect hundreds of millions of individuals around the world. The majority of these rare diseases have no effective treatment, leading to a significant unmet medical need.

Historically, pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies have lacked substantial incentive to invest the millions of dollars required for the necessary research that may bring a new rare disease therapy to market. Since the definition of a rare disease is one that affects less than one in every 2,000 individuals in Europe, and less than one in 200,000 in the US, patient populations for these rare diseases are often small, making clinical trials and drug development even more challenging.

In 1983, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) established the Orphan Drug Act to provide drugmakers with financial incentives and other perks – like seven years of market exclusivity – to encourage rare disease research. In the past 35 years, the Orphan Drug Act has gone a long way to making clinical development for rare disease indications more common, leading to the launch of an array of small biotechs and divisions within big pharma focused solely on rare disease research.

According to the pharmaceutical trade organization PhRMA, over 600 orphan drugs have been approved by the FDA since the inception of the Orphan Drug Act. Still, only five percent of rare diseases have an approved treatment. But with 560 drugs and biologics in the pipeline with rare disease indications, there’s no shortage of drive when it comes to treating and potentially curing these conditions.

Since rare diseases are often difficult to diagnose due to the overlap of symptoms with more common conditions, biopharmaceutical companies face an uphill battle when it comes to developing treatments and recruiting enough patients to clinical trials in order to test those drugs. Drugmakers are increasingly looking to identify biomarkers that can be detected using purpose-built companion diagnostics in order to facilitate more efficient diagnoses of rare diseases.

Recent approvals for orphan drugs has helped to establish the rare disease market as a lucrative one for drugmakers. In early 2018, the FDA approved what is currently the most expensive drug in the US: Spark Therapeutics’ Luxturna. Priced at $425,000 per eye – a total of $850,000 per patient – Luxturna is a gene therapy designed to treat patients with a rare form of inherited blindness known as Leber congenital amaurosis which is associated with a confirmed biallelic RPE65 mutation.

Since many rare diseases still lack an effective cure, EURORDIS highlighted five of those conditions in their promotion of Rare Disease Day 2018 by sharing patient and researcher stories. These five conditions offer drugmakers the opportunity to be first-to-market with therapies capable of addressing the underlying genetic basis of the rare disease and providing patients with better outcomes.

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome is actually a group of 13 different connective tissue disorders based on various symptoms and genetic mutations in the gene responsible for collagen synthesis. Each subtype affects a different part of the body containing connective tissue, including the muscles, blood vessels, tendons and gums. The disease affects between one in 2,500 and one in 5,000 individuals and has symptoms which include joint hypermobility and skin hyperextensibility. The ability of joints to hyperextend means patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome are at risk of recurrent dislocations, joint pain and early-onset osteoarthritis. These patient’s highly-elastic skin leads to severe bruising, scarring and poor wound healing.

Currently, patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome are treated with medications aimed at addressing the symptoms of the condition as opposed to directly targeting the underlying pathology of the disease. For example, treatment of hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome – just one of the 13 subtypes – includes pain medications, physical therapy, and in some cases, mobility devices such as wheelchairs to help patients get around while protecting fragile joints from damage.

According to ClinicalTrials.gov, a US registry of both domestic and international studies, there are 12 active studies investigating Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Just five of these studies are interventional, with the majority assessing the ability of devices, such as compression garments, to help stabilize joints and reduce joint pain.

On Rare Disease Day 2018, EURORDIS featured Mirina, a girl diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome at the age of four.

“She has found that in education there can be a lack of understanding of Ehlers Danlos, in part due to its rarity,” says the EURORDIS profile of Mirina. “Mirina’s disease is also not visible which meant that in some cases the effects of her disease were not taken seriously by her teachers. She believes that training adults about rare diseases is the key to changing the attitudes.”

Marfan Syndrome

Like Ehlers Danlos syndrome, Marfan syndrome also affects the connective tissue found throughout the body. Because of this similarity, patients with Marfan syndrome are often misdiagnosed as having Ehlers Danlos syndrome, and vice-versa.

A genetic analysis is often performed to differentiate between the two conditions, as Marfan syndrome is caused by mutations in the gene responsible for production of the fibrillin-1 protein, called the FBN1 gene. While the majority of cases of Marfan syndrome are the result of an inherited mutation, around one-quarter of them are caused by de novo mutations.

With an incidence of one in every 5,000 individuals, Marfan syndrome is on the more common end of the rare disease spectrum. While symptoms of the condition vary among individuals, most patients display heart abnormalities, including aortic enlargement, which can lead to potentially life-threatening cardiac complications.

Treatments for Marfan syndrome are largely dependant on a patient’s symptoms and include a wide range of pharmacological and surgical options. Beta blockers, calcium channel blockers and ACE inhibitors are all commonly prescribed to slow heart rate and reduce stress on the aorta. Valve graft surgery coupled with blood thinners is another treatment option for Marfan syndrome patients at risk of suffering an aortic tear due to dilation of the artery.

According to ClinicalTrials.gov, there are currently four active studies involving patients with Marfan syndrome. Two of these studies are interventional, one of which is assessing the benefits of an exercise rehabilitation program, while the other is investigating an intraocular lens, developed by Ophtec USA, aimed at correcting vision problems in patients with Marfan syndrome whose lenses have been dislocated due to the degradation of surrounding ligaments.

On Rare Disease Day 2018, EURORDIS shared the story of Yara, a researcher specializing in Marfan syndrome.

“Yara hopes that as research progresses and awareness improves, we will learn more about rare diseases and the number of rare diseases with treatment will increase,” says Yara’s profile. “At the moment only 5 percent of rare diseases have treatment and there are many gaps in scientific and medical knowledge. But Yara believes that if health care providers, researchers and patients work closely together great progress will be made in the future.”

Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva

Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP) leads to extra-skeletal bone formation due to the replacement of connective tissue and skeletal muscle with bone tissue. The incidence of this disorder is just one in two million, classifying it as an ultra-rare disease.

Unlike Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and Marfan syndrome, FOP is often caused by a mutation in the ACVR1 gene which is conserved among individuals with the disorder. The disease is often diagnosed during childhood, with the process of extra-skeletal bone formation worsening as the individual ages, eventually affecting mobility, the ability to eat and breathe.

Corticosteroids, like predinisone, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are often the first line of treatment to relieve painful symptoms associated with a flare-up during which more tissue is replaced by bone.

Six studies involving patients diagnosed with FOP have been registered on ClinicalTrials.gov, four of which are interventional. Half of the studies are investigating the effects of palovarotene, a retinoic acid receptor gamma (RAR-γ) agonist, on extra-skeletal bone formation, sponsored by Clementia Pharmaceuticals. Like other rare diseases, natural history and registry studies are often as important as clinical trials to improve understanding of the condition and help investigators identify eligible patients for future interventional studies.

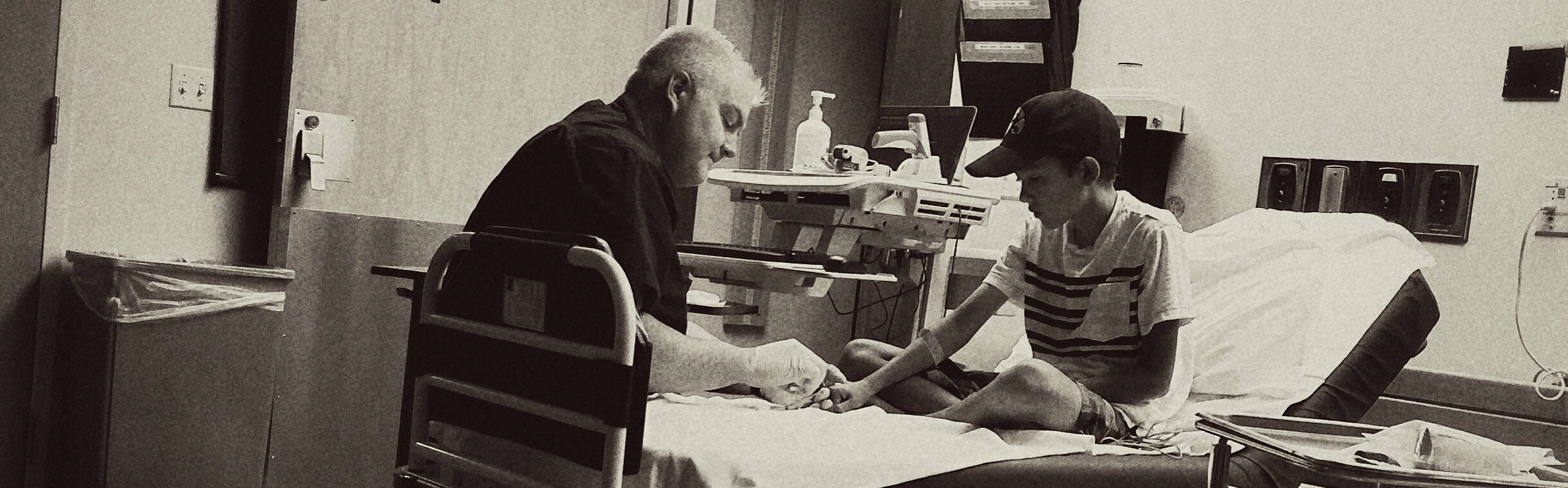

EURORDIS highlighted the stories of father and son, Antoine and Alexandre, who have found that patient groups have been integral in understanding and coming to terms with Alexandre’s diagnosis with FOP.

“He outlines the two main roles patient groups play in supporting those living with rare diseases,” says the write-up on Antoine and Alexandre. “Firstly, they relay the experiences of their members who can help those recently diagnosed understand the situation and challenges of living with the rare disease. Secondly due to the isolation felt by many rare disease patients, these groups can promote solidarity of patients, to make those living with rare diseases feel like one of many.”

Leber Hereditary Optic Neuropathy

A disease characterized by the sudden loss of central vision, Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) usually occurs in one eye first, closely followed by the other. Individuals diagnosed with LHON often retain their peripheral vision, however the severe loss of central vision makes it near-impossible for them to read or recognize other people’s faces.

The global incidence of LHON is less than one in 15,000 individuals, with 95 percent of patients who experience symptoms losing their vision before they turn 50. The disease is caused by mutations in mitochondrial DNA, including in the MT-ND1, MT-ND4, MT-ND4L, and MT-ND6 genes.

As mitochondrial DNA is only inherited from an individual’s mother, women with LHON are the only parents who can pass the condition onto their children. Men diagnosed with the disease cannot pass the mutation along to their offspring as they make no contribution of mitochondrial DNA to the embryo.

Interestingly, not all individuals who carry one of these mutations go on to develop symptoms of vision loss due to LHON; over 85 percent of women and 50 percent of men retain normal vision throughout their adult life.

Treatment of LHON largely relies on visual aids and other disease management tools that don’t address the underlying genetic cause of the condition. In Europe, Raxone (idebenone), developed by Swiss pharmaceutical company Santhera, remains the only drug approved to treat Leber hereditary optic neuropathy, however the drug has not yet been approved by regulators in the US.

The drug is an antioxidant which is believed to improve mitochondrial function in patients with the condition. As such, it does not correct the mutation responsible for LHON, but only addresses its effects.

In all, 16 studies of LHON have been registered on ClinicalTrials.gov, 11 of which are interventional. Santhera is currently recruiting for a long-term safety and efficacy study for Raxone, while many of the other studies involved gene therapy candidates developed by companies like GenSight Biologics.

Annie, a woman who developed LHON at the age of 44, was profiled for this year’s Rare Disease Day.

“When Annie first went to hospital she remembers the traumatising speed of her losing her eyesight as she says she had the impression that everything was disappearing in front of her,” says the profile of Annie. “Over the past 25 years she has learned how to do more and more in spite of her disease as she now is able to walk confidently and look at photos with the help of an enlargement screen.”

Congenital Myasthenic Syndrome

There are three subtypes of congenital myasthenic syndrome, all of which cause muscle weakness and fatigue. These subtypes have different treatment options and include the postsynaptic, synaptic and presynaptic types which account for up to 80, 15, and 8 percent of all cases, respectively.

Congenital myasthenic syndrome affects about one in every 5,000 individuals in the US and is most often inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. Since individuals with the condition have a decrease in acetylcholine receptors on muscle fibers of up to 80 percent, they have reduced capacity to use their muscles to react to nerve impulses. The presence of antibodies is thought to be responsible for this loss of acetylcholine receptors. Nearly all muscles in the body are affected by this deficit, leading to symptoms such as muscle weakness in the limbs, breathing problems, difficulty eating and vision problems.

Unlike many of the other rare diseases detailed in this article, patients with congenital myasthenic syndrome actually have multiple, effective treatments to chose from. While none of these drugs can cure the condition, they can remove or reduce the damaging action of the antibodies to improve muscle function.

Valeant Pharmaceuticals’ Mestinon (pyridostigmine), Genetech’s Cellcept (mycophenolate mofetil) and Prometheus Laboratories’ Imuran (azathioprine) are just a few of the available pharmacologic treatment options for congenital myasthenic syndrome. Interestingly, some patients may experience spontaneous improvement in symptoms without undergoing treatment.

ClinicalTrials.gov returns seven results for ongoing studies in congenital myasthenic syndrome, two of which are open to patients who would not normally qualify for clinical trial participation under the FDA’s Expanded Access program. Four of the registered studies are investigating the use of 3,4-Diaminopyridine in the treatment of congenital myasthenic syndrome, two of which list Jacobus Pharmaceutical as a collaborator.

At five years old, Enzo was diagnosed with congenital myasthenic syndrome when he was five months of age and is the youngest rare disease patient featured by EURORDIS this year.

“Congenital myasthenic syndromes affect the way the motor nerve controls the movement of the muscles which act,” says Enzo’s write-up. “As a consequence, Enzo’s eyelids remain half closed and Cindy, his mother, tells us that she is often told that he looks tired and that he needs rest by people in the street. Because of how the rare disease affects his muscles, Enzo fatigues easily and so uses a wheelchair most of the time, though he loves to walk for short distances where possible.”

While these five rare diseases represent a significant unmet medical need for patients, and a potential target for orphan drug development for pharma and biotech companies, there are thousands of other rare diseases that also have no cure. In connection with this, precision medicine appears to be the prevailing trend for the future of drug development. Treatment options for conditions like certain types of cancers, which were once considered to be common, are effectively being treated as rare diseases in order to develop more personalized, targeted therapies for patients.

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN