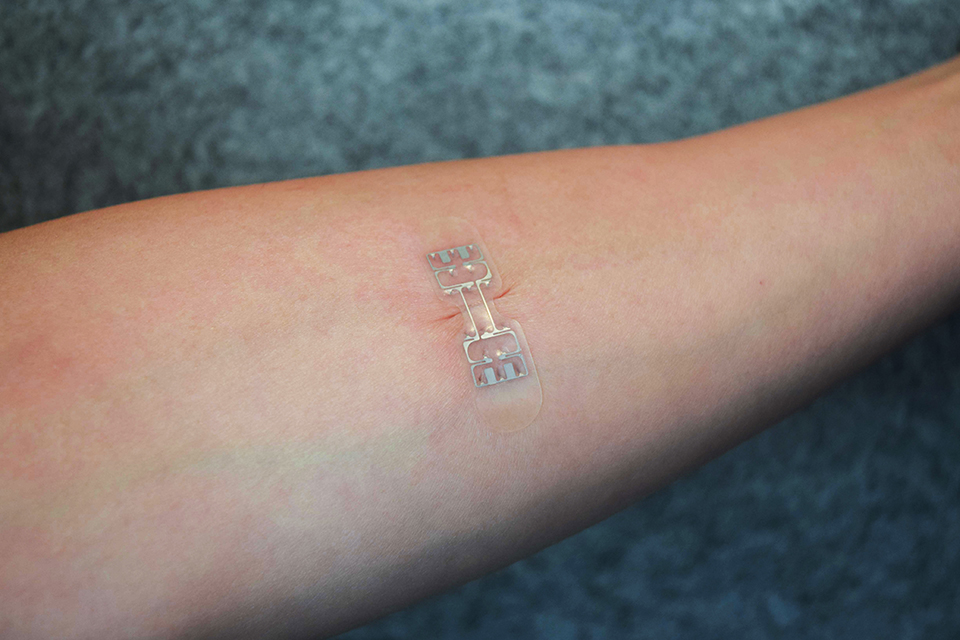

A hemorrhage can quickly become fatal if the bleeding is left uncontrolled, however few drugs can quickly and effectively stop blood loss and promote wound healing. Now, researchers from the Inspired Nanomaterials and Tissue Engineering Laboratory at Texas A&M have developed an injectable biomaterial that acts as a “liquid bandage” that can activate the blood clotting response and slow bleeding.

“Injectable hydrogels are promising materials for achieving hemostasis in case of internal injuries and bleeding, as these biomaterials can be introduced into a wound site using minimally invasive approaches,” said Dr. Akhilesh K. Gaharwar, assistant professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Texas A&M University. “An ideal injectable bandage should solidify after injection in the wound area and promote a natural clotting cascade. In addition, the injectable bandage should initiate wound healing response after achieving hemostasis.”

The injectable hydrogel developed by Gaharwar and his colleagues consists of kappa-carrageenan – a thickening agent derived from seaweed that is commonly used as a thickener in food applications – and nanosilicates. In addition to reducing the time it takes for blood to clot, the hydrogel can also be impregnated with therapeutic drugs that can be delivered to the wound site and slowly released.

Hydrogels are made up of hydrated polymers in a structure which mimics human tissue and allows it to be applied to the wound as an injectable substance. Because of the addition of the nanosilicates, the hydrogel contains hemostatic properties which promotes platelet binding and triggers the blood clotting signal cascade.

“Interestingly, we also found that these injectable bandages can show a prolonged release of therapeutics that can be used to heal the wound” said Giriraj Lokhande, a graduate student in Gaharwar’s lab and first author of the paper which was published in the journal Acta Biomaterialia. “The negative surface charge of nanoparticles enabled electrostatic interactions with therapeutics thus resulting in the slow release of therapeutics.”

The research team believe their injectable bandage has a military application with the potential to prevent hemorrhage after a soldier has sustained a wound on the battlefield. They envision their injectable hydrogel could be self-administered to the wound site to stop the bleeding and hopefully prevent hemorrhage-related death.

According to the US Army’s Combat Casualty Care Research Program, hemorrhage has accounted for almost half of all combat deaths since World War II, suggesting a great unmet need for a medical intervention to stop the bleeding faster.

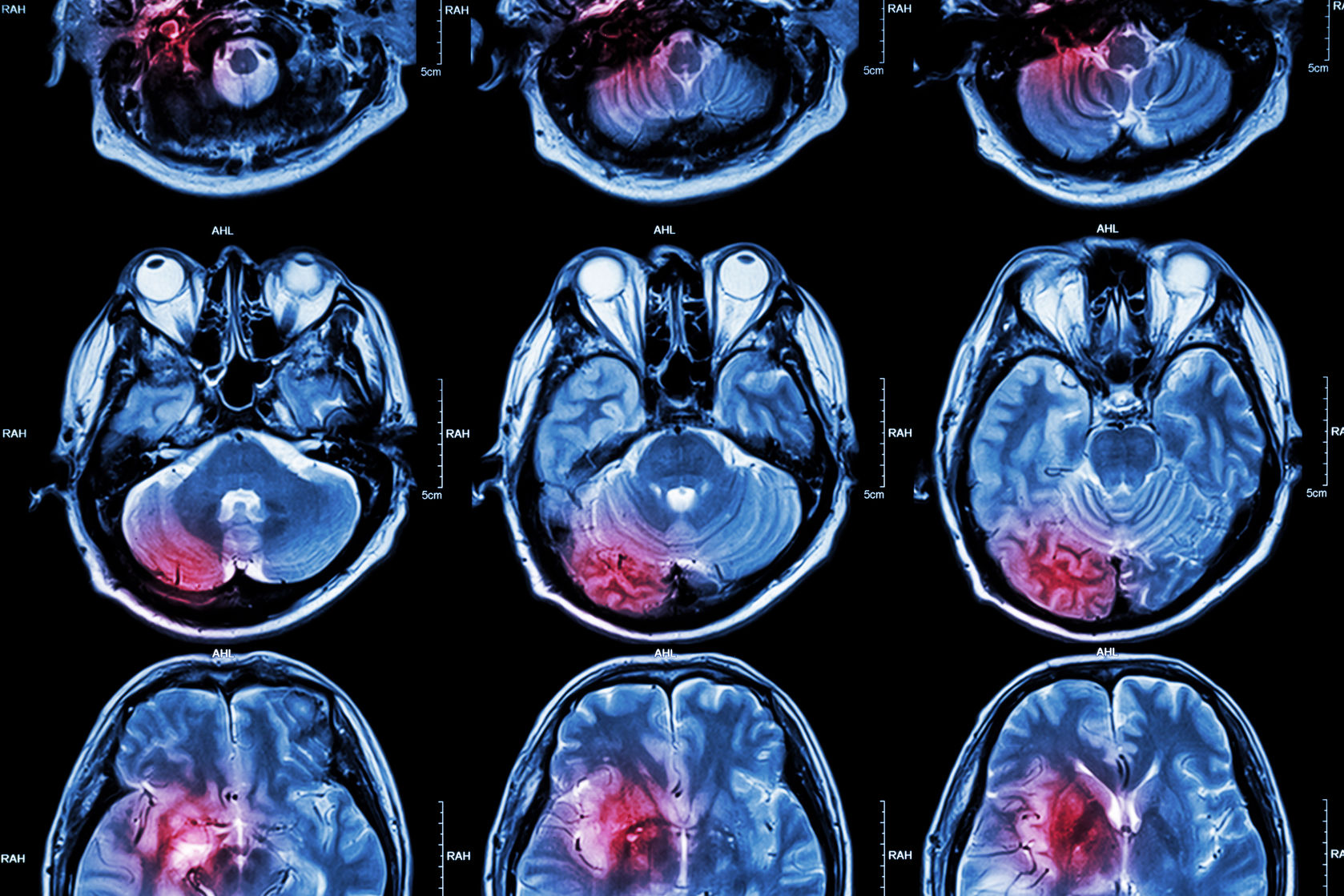

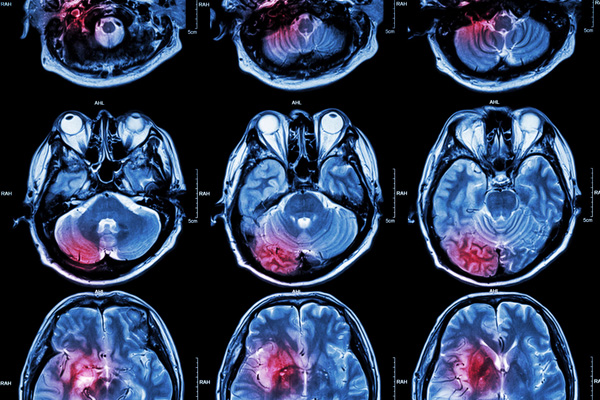

The hydrogel may also be helpful in the emergency room where doctors may need to control bleeding in patients who have sustained an injury. What’s more, since many patients at risk of suffering recurrent strokes are prescribed blood-thinner drugs like Warfarin to block the coagulation response, these individuals are at a higher risk of uncontrolled bleeding events. While specific reversal agents are often used in the event that a patient taking these anticoagulant medications requires surgery, the injectable hydrogel developed by Gaharwar and his colleagues could also control bleeding in these patients.

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN