Imagine a classroom of preschoolers. Almost right away, you can learn a lot about children’s personalities based on their speech and behavior. When it comes to reserved children, however, it’s often hard to tell if the reserved child is sad or having a bad day, or if they are showing signs of psychopathology.

Anxiety and depression can afflict children as young as age three. Research suggests that these children might display internalizing behaviors like bottling up their anger, fear or distress and they display high levels of effortful control – opting for a more subdued response over a dominant response.

Understandably, parents, teachers and doctors have a hard time recognizing these internalizing symptoms, but the consequences of them can be profound. Children with internalizing disorders will likely have a difficult time with school and making friends, and are at an increased risk for developing substance abuse later in life.

Identifying internalizing disorders early can potentially alter the course of a child’s life.

“Because of the scale of the problem, this begs for a screening technology to identify kids early enough so they can be directed to the care they need,” said Ryan McGinnis, a biomedical engineer at the University of Vermont.

In an article published in PLOS One, McGinnis and collaborators from the University of Vermont and the University of Michigan developed and tested a novel screening tool that identifies children with internalizing disorders through their movement.

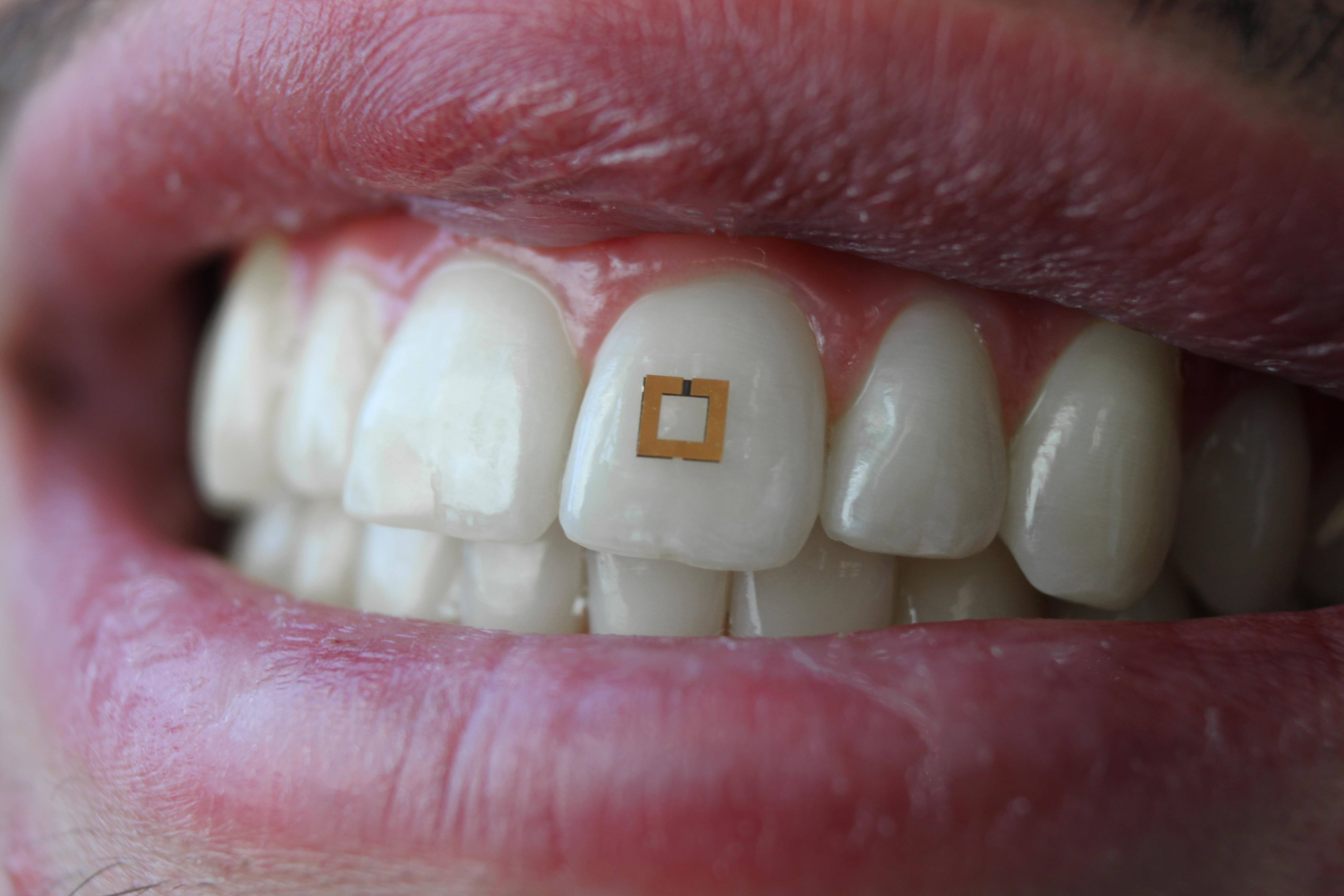

Movements are sensed by a wearable device, then analyzed by a machine learning algorithm which determines if that movement is linked to anxiety or depression.

The researchers created a scenario that would elicit anticipation or anxiety and video-recorded the children’s behavior. What interested the researchers were the moments before the surprise was revealed – specifically, how the children moved.

With just 20 seconds of recorded data, the sensor was able to accurately identify children with internalizing disorders over 80 percent of the time.

But how did the sensor know? The sophisticated algorithm determined that the act of turning away suggested that a child might be anxious, and thus would be coded as having an internalizing disorder.

“Something that we usually do with weeks of training and months of coding can be done in a few minutes of processing with these instruments,” said Ellen McGinnis, a clinical psychologist at the University of Vermont and Ryan McGinnis’ partner.

Due to children’s limited ability to express complex emotions, it is hard to capture signs of anxiety and depression at home or in the classroom. Harnessing machine learning technology to aid with detection is a step in the right direction.

“It’s exciting to move the field along with technology,” said Maria Muzik, a researcher at the University of Michigan.

The researchers hope to improve their device by adding a voice analysis component. A child’s tone of voice, intonation and choice of words could potentially reflect internal distress.

Before the sensor and algorithm are distributed in classrooms, researchers should be cognizant of the limitations of machine learning. As Dr. John Touros from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, points out to Mashable, “machine learning is only as good as the data it’s trained on.” In other words, a bigger sample size with diverse groups of children will help make the algorithm more robust.

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN