Why did the genetically modified chicken cross the road? To lay drug-filled eggs, of course.

The transgenic chickens, bred by researchers at the University of Edinburgh’s Roslin Institute and Roslin Technologies, could lay eggs containing high concentrations of human proteins that could treat cancer, viral infections and tissue damage.

Besides laying therapeutic eggs, the chickens look and behave like normal farm animals. In fact, they might be better off this way.

“They live in very large pens. They are fed and watered and looked after on a daily basis by highly trained technicians, and live quite a comfortable life, said Dr. Lissa Herron, first author of the research study published in BMC Biotechnology. “As far as the chicken knows, it’s just laying a normal egg. It doesn’t affect its health in any way, it’s just chugging away, laying eggs as normal.”

Transgenic animals play an important role in drug discovery and research. In the early days of recombinant DNA technology, scientists introduced modified strands of DNA into yeast and bacteria to mass produce a particular protein. It soon became apparent that these simple organisms could not manufacture human proteins that are much larger and more complex, despite carrying the right genetic information.

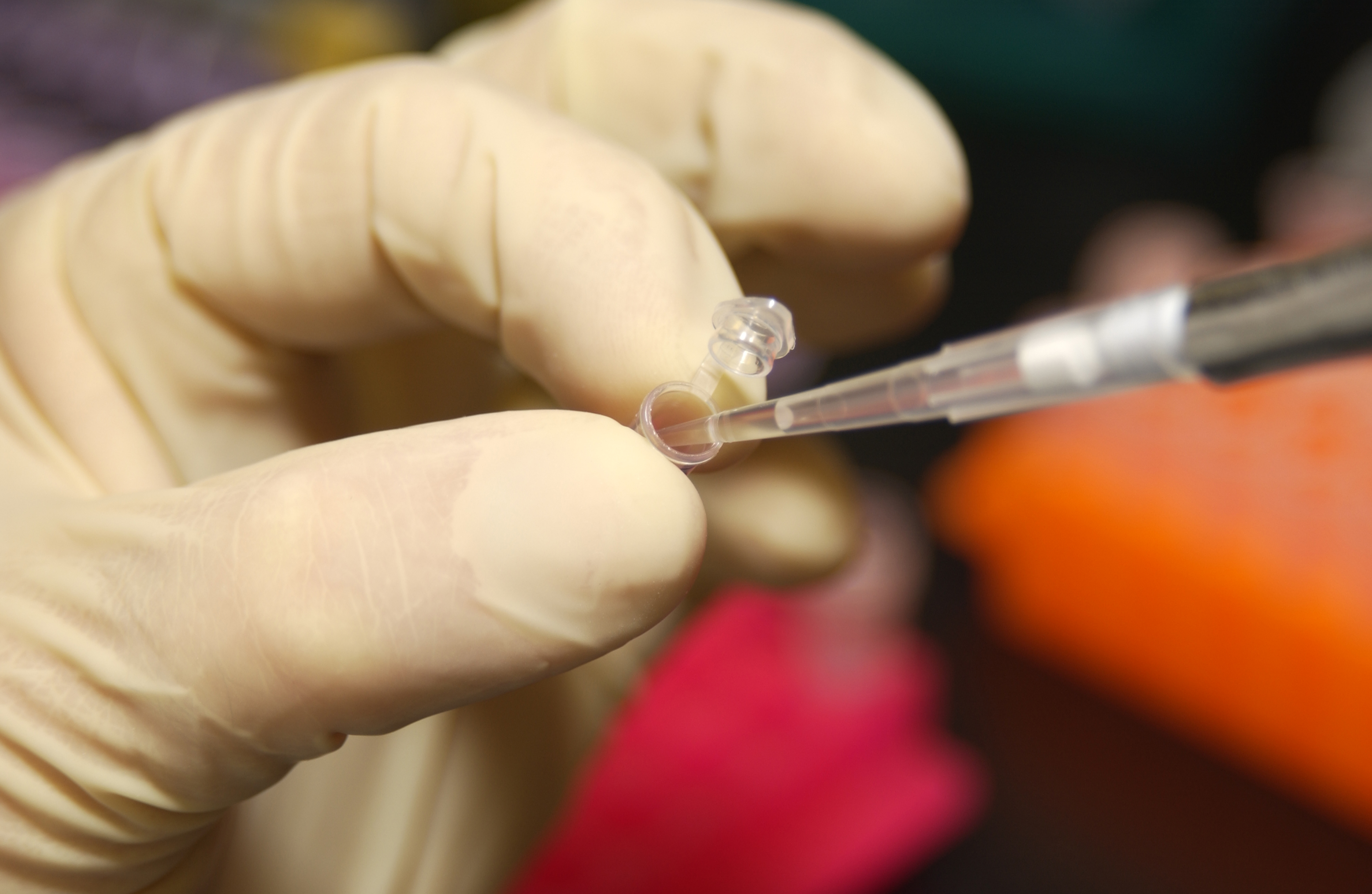

Presently, the researchers engineered the chickens to produce interferon alpha 2a (IFNα2a) and macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) in their egg whites.

Although not as efficient as microorganisms, transgenic animals can still solve a lot of problems encountered in modern drug manufacturing. They are generally cheaper to maintain compared to a sterile drug facility and the high yield of milk or eggs balances the cost of animal care.

Take antibodies, for example, which are notoriously expensive to manufacture. The cost of producing enough monoclonal antibody to service the entire human population is approximately $300 per gram, according to a 2013 review. The same quantity of antibody can be produced in the milk of 210 goats at one-third of the cost.

In the present study, the authors found that three eggs laid by their genetically engineered chickens would contain enough human protein for one dose of drug. If a single hen lays 300 eggs per year, they could produce enough doses of the drug for commercialization.

“Production from chickens can cost anywhere from 10 to 100 times less than the factories. So hopefully we’ll be looking at least 10 times lower overall manufacturing cost,” said Dr Herron.

However, the use of transgenic animals for drug development still come with some caveats. For example, not every human protein can be made this way, as certain hormones and cytokines might have negative effects on the health of the animal.

Large mammals like goats, have long gestation periods and low fecundity, limiting the frequency and volume of milk production. The researchers report that their method is more efficient and cost-effective than previous attempts.

Genetic modification is gaining traction in both the pharmaceutical and agricultural industries. ATryn (by GTC Biotherapeutics) was the first drug produced by using a transgenic animal, achieved regulatory approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2009 for the treatment of hereditary antithrombin deficiency. On the agricultural side, farmers have long used genetically modified seeds to produce crops that bear more fruit, are resistant to pathogens and have better nutrient profiles. Similarly, genetic modification of animals can yield healthier livestock and plumper pigs.

What’s stopping this field from exploding is consumer reluctance to trust genetically modified organisms (GMOs). According to a consumer survey, nearly half of the responders say they avoid products with GMOs. What would these people think if their next anti-arthritis drug came from a GMO chicken egg?

The genetically engineered hens (nor their eggs) from this study will not be found at your local grocery store anytime soon. This proof-of-principle research opens the doors to novel drug manufacturing strategies.

What do you think about the production of pharmaceutical proteins by transgenic animals? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN