Biomedical engineers at the University of Minnesota have successfully implanted artificial blood vessels capable of further growth, in young lambs. If the promising results from the animal studies can be reproduced in humans, the blood vessel grafts could reduce the number of surgeries needed to correct congenital heart defects in children.

Bioengineers have long struggled with developing blood vessels that will continue to grow after they have been implanted into the patient. The groundbreaking research – which has potentially overcome this hurdle – was published in the journal, Nature Communications.

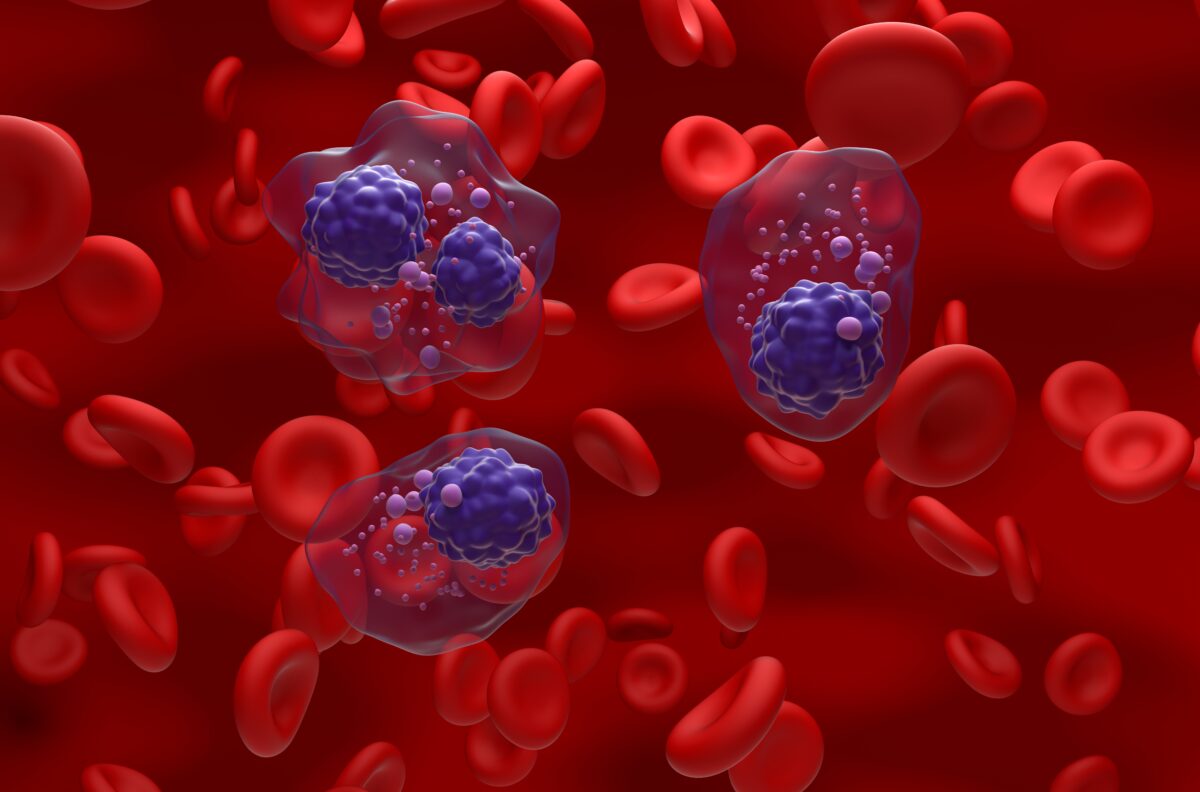

Using skin cells collected from a post-natal donor, the researchers were able to generate hollow tubes much like the blood vessels found throughout the body. To decrease the risk of implant rejection by the recipient, the donor cells were removed from the bioengineered blood vessels.

By removing the donor cells, the artificial vessels could also be stored for longer periods of time. When the researchers grafted these vessels in the young lamb, the implant became repopulated by the recipient’s cells, which could allow it to further grow and develop within the animal.

“This might be the first time we have an ‘off-the-shelf’ material that doctors can implant in a patient, and it can grow in the body,” said Dr. Robert Tranquillo, Professor in the University of Minnesota’s Department of Biomedical Engineering. “In the future, this could potentially mean one surgery instead of five or more surgeries that some children with heart defects have before adulthood.”

To develop the artificial blood vessels for this study, Tranquillo and his colleagues combined sheep-derived skin cells, fibrin and cell culture nutrients in a bioreactor. The cells and fibrin were coaxed into forming a tube, and the custom-developed bioreactor was designed to create blood vessels that are stronger than native arteries.

After up to five weeks of incubation, the cells were removed from the tubes using special detergents. The resulting cell-free matrix did not elicit an immune response from a five week old lamb when a section of its pulmonary artery was replaced with the artificial blood vessel.

“What’s important is that when the graft was implanted in the sheep, the cells repopulated the blood vessel tube matrix,” said Tranquillo. “If the cells don’t repopulate the graft, the vessel can’t grow. This is the perfect marriage between tissue engineering and regenerative medicine where tissue is grown in the lab and then, after implanting the decellularized tissue, the natural processes of the recipient’s body makes it a living tissue again.”

At just under one year of age, the sheep’s artificial blood vessel graft had grown by 56 percent in diameter, with a 216 percent increase in its blood volume capacity. In addition, the amount of collagen in the graft increased by 465 percent leading researchers to conclude that the graft had not just stretched but had actually grown.

“We saw growth and none of the bad things happened,” said Tranquillo. “The results are very encouraging.”

As no adverse effects – such as calcification, vessel narrowing or clotting – were observed by the researchers, they plan to continue their study. Tranquillo and his team hope to determine how feasible an application for US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval to start human clinical trials would be for their bioengineered blood vessel.

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN