While the approval pathway for biosimilar products was established 12 years ago, there are still misconceptions about how biosimilars are approved, biosimilarity versus interchangeable status and which patients can be treated with biosimilars. In order to fact-check some of these misconceptions, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently hosted a webinar on biosimilar and interchangeable biological products to help healthcare professionals understand more about these treatment options.

What is a Biosimilar?

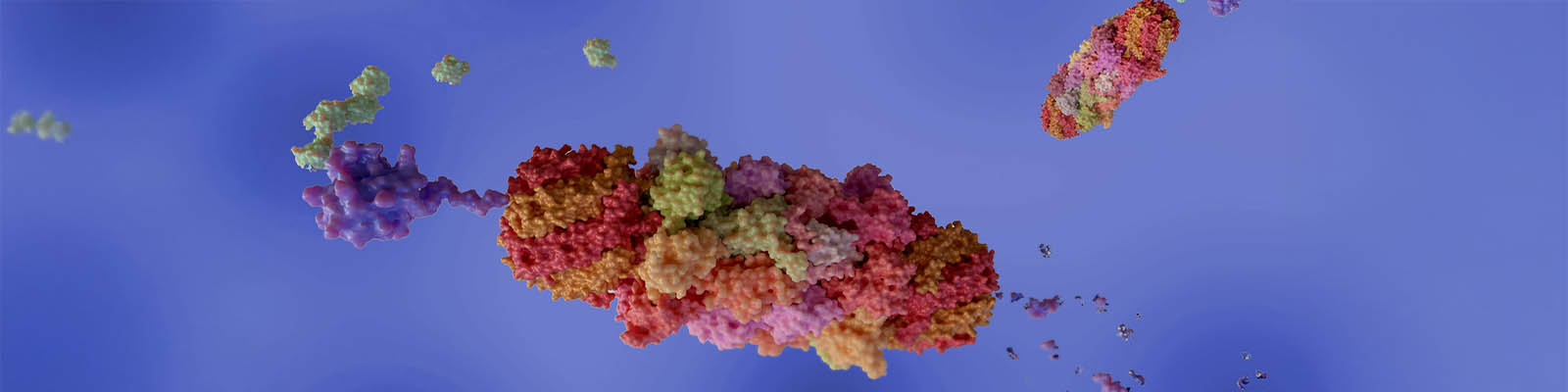

Biosimilars are the “generic” drugs of the biopharma world. They include proteins, monoclonal antibodies and vaccines that are considered to be “highly similar” to biological products that have already been approved by the FDA. Biosimilars must show no clinically meaningful differences from their reference products in terms of both safety and effectiveness in order to be classified as highly similar.

Like generic forms of synthetic pharmaceuticals, biosimilars have the advantage of being less costly compared to their branded counterparts. As biologics have the reputation of being expensive due to their complex nature and production, biosimilars have the ability to improve market access to patients and payors who would otherwise be unable to afford these drugs.

To date, the FDA has approved 29 biosimilars, 19 of which are currently being marketed. Genentech’s blockbuster breast cancer drug Herceptin (trastuzumab) holds the top spot for having the most biosimilar versions on the market with five highly similar alternatives. While there are currently six biosimilars for AbbVie’s Humira (adalimumab) that have been approved by the regulator, the company’s patents prevent biosimilars from being launched until 2023.

What is an Interchangeable Biological Product?

As a subset of biosimilars, interchangeable biological products can be substituted for the reference product at the pharmacy level, without the input of the prescribing physician. According to the FDA, in order for a biosimilar to be granted interchangeable biological product status, it must be shown “to produce the same clinical result as the reference product in any given patient.”

Crucially, biosimilars manufacturers must also demonstrate that their product’s safety and efficacy profile won’t go down if a patient switches back and forth between the biosimilar and the reference product during the course of treatment.

As yet, the FDA hasn’t approved any interchangeable biological products, but the promise of pharmacists being able to fill a prescription with a biosimilar in the place of a prescribed reference product could be alluring to biopharmaceutical companies.

So far, few biopharma companies have publicly disclosed that they’re actively seeking interchangeable status for their biosimilar products. Boehringer Ingelheim’s Cyzelto, a biosimilar to Humira, is one of the only products that is known to be looking for interchangeability.

Last year, Biocon Biologics and Mylan announced they’d be seeking interchangeable status for their long-acting insulin product Semglee, developed to be an alternative to Sanofi’s Lantus (insulin glargine). While Semglee was actually approved as a biologic in its own right through the FDA’s traditional new drug application pathway in the US, the company is also looking to gain biosimilar status.

MYTH: Biosimilars are exactly the same as their reference product.

Owing to their large molecular size, complexity and the fact that they’re produced in living organisms, such as bacterial and yeast cell culture, biologic products represent a mixture of proteins with slight variations. This means that there are inherent differences between batches of the same biologic; however, manufacturers aim to keep the ratios of molecular variations consistent across each lot.

“Although variation is expected due to the complexity of these products, it’s controlled, so there is consistency within an allowable range across batches and over time,” says Nina Brahme, PhD, MPH, a clinical analyst at the FDA and one of the presenters in the regulator’s recent webinar. “Because most biologics are mixtures of variants, they really can’t be copied exactly.”

Unlike generic drugs, the complex nature of biological products means that it’s impossible for biosimilars to be identical to their reference product. The FDA requires manufacturers to characterize the structure and bioactivity of a proposed biosimilar to demonstrate that it’s highly similar to the innovator biologic.

The regulator allows biosimilars to show slight differences in clinically inactive components of a product. Minor differences in excipients or other components designed to stabilize the biologic are permitted.

MYTH: Clinical pharmacology studies of biosimilars aim to establish safety and effectiveness.

Unlike small-molecule generic drugs, biosimilars do not need to demonstrate bioequivalence to the innovator product. The assessment of proposed biosimilars is focused on provided evidence that it is highly similar to the reference product with no clinically meaningful differences.

“Biosimilars are attempting to show that they are like the reference product,” says Brahme. “In a stepwise fashion, the pyramid of evidence is built based on extensive comparisons.”

In fact, innovator biologics and their biosimilars are approved through two different regulatory pathways. When a new biologic drug is in development, innovator biopharmaceutical companies have the burden of establishing the de novo safety and efficacy of the product through analytical testing, nonclinical studies, clinical pharmacology and the phases of clinical trials as established by the 351(a) Biologics License Application (BLA) process.

“The biosimilar pathway is, at times, described as an ‘abbreviated pathway’ because the amount of clinical data needed is less than if the standalone pathway were pursued for the same product. That’s important because those big clinical studies are expensive to run,” says Brahme.

In contrast, biosimilars are approved through the abbreviated 351(k) BLA which emphasizes the analytical and animal studies stages of development to provide data that demonstrates the similarity to the reference product. Biosimilars developers may also be required to conduct PK/PD studies and assess the immunogenicity of their product prior to approval.

MYTH: Interchangeable biological products have achieved a higher level of biosimilarity.

Some prescribers and pharmacists have been hesitant to give patients biosimilar forms of biologic drugs over concerns that they may not be as safe or effective as the branded product. In fact, some healthcare professionals have expressed that they’re waiting until a biosimilar achieves interchangeable biological product status before they’re willing to prescribe a biosimilar.

The fact is, when an interchangeable biological product is eventually approved by the FDA, it will have undergone additional testing to show that it “is expected to produce the same clinical result as the reference product in any given patient,” a requirement laid out by the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act. However, this will not mean that the interchangeable biological product has achieved a higher level of biosimilarity compared to other highly similar products.

“If the FDA licenses an interchangeable, that means that switching between the interchangeable and the reference doesn’t increase the safety risk or decrease the effectiveness compared to using the reference only,” says Brahme.

While none of the approved biosimilars in the US have been granted interchangeable status just yet, this doesn’t mean that pharmacists can’t help their patients access lower-priced alternatives to branded biologics. Pharmacists are not permitted to make the decision of filling a biologics prescription with a biosimilar — as they could for a generic equivalent to a branded pharmaceutical — but they can contact the prescribing physician to discuss the appropriateness of making the switch.

And while improved access to biosimilars is the goal of interchangeability, it is possible that some biopharmaceutical companies will choose not to seek interchangeable biological product status for business reasons, such as costs associated with any additional clinical trials that may be needed.

MYTH: Treatment-experienced patients cannot be prescribed biosimilars.

If a patient has already been treated with a branded biologic, some healthcare professionals aren’t sure whether they can switch their prescription to the biosimilar version once it’s available. According to the FDA, both treatment-experienced and treatment-naïve patients can be prescribed biosimilars.

Applicants may be required to provide data on the safety of switching patients one time from a reference biologic to the biosimilar. This ensures that when the biosimilar is approved, it’s safe to prescribe to those who have previously been treated with the biologic.

MYTH: Biosimilars must be approved for all indications of the reference product.

There are many reasons why the developer of a biosimilar would choose not to seek approval for all indications of a reference product, but this decision has no effect on its ability to be licensed for a subset of indications. For example, ongoing patent litigation may dictate which indications are pursued for a biosimilar.

Sometimes the decision not to pursue a specific indication lies in the inability of the FDA to approve biosimilars for that use. Brahme explains, “Some indications approved for the reference product are still protected under orphan exclusivity, and so FDA is not able to license biosimilars for those indications.”

MYTH: Applicants can seek approval for indications above and beyond those granted to the reference product.

While biosimilars companies can choose which indications they want to pursue approval for, they are not permitted to apply for other indications outside of the scope of those previously granted to the reference biologic.

Since trials designed to demonstrate the highly similar nature of biosimilars aren’t extensive enough to show a product’s efficacy in treating conditions outside the indications approved for the reference product, applicants would have to go through the de novo pathway to gain approval for new indications, and would thus not be considered to be biosimilars but biologic products in their own right.

MYTH: Biosimilars must have the same labeling as their reference product.

Biosimilar labels will always differ from the label on their branded counterparts because they include a Biosimilarity Statement in the Highlights section. This statement explains the nature of its relationship to the reference product, including whether the product is interchangeable.

While the label on a biosimilar product is not required to be the same as the reference product, the FDA does recommend that relevant information found on the innovator biologic be included. This includes information on approved indications and risk statements applicable to both the biosimilar and its reference product.

Significantly, insulin was deemed to be a biologic as of March 23, 2020, making it a reference product for the development of biosimilar versions. This replaces the previous approval pathway for insulin drugs and their analogs which have historically been reviewed as new drug applications under section 505(c) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act).

Though the average cash price of various insulins dipped by almost six percent last year, the general trend for the cost of insulin has been steadily climbing for the last several years. According to a statement issued by the FDA following the reclassification of insulin as a biologic, the move is expected to have a beneficial effect on healthcare costs for payors as insulin competitor products come to market. Their analysis has shown that biosimilars have historically been launched with a list price up to 35 percent less than the reference biologic, offering significant savings to patients and insurers.

But when it comes to interchangeable products, some have raised the question of whether this designation is even relevant in today’s biosimilars landscape. As an article published in Biosimilar Development points out, most biosimilars are currently administered to patients in hospitals as opposed to being distributed directly to the patients themselves through retail pharmacies. This puts the prescribing decisions in the physician’s hands, eliminating the need for biosimilars developers to pursue interchangeable status when the hospital’s pharmacy team wouldn’t be making patient-level decisions to switch between biologics and biosimilars anyway.

With this in mind, perhaps insulins are the most relevant benefactor of the interchangeable product pathway, as the ability of a pharmacist to fill a patient’s prescription for long-acting insulin glargine with a biosimilar — or interchangeable — version would result in cost-savings for the patient as well as skyrocketing sales for copycat biopharmaceuticals.

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN