Many nutritional classification systems rate the overall health of a food product based on the number of nutrients it contains. However, a growing number of researchers and food epidemiologists believe this system to be too broad.

As more studies find connections between processed foods and their negative effects on health, a France-based start-up known as Siga, has created a scientific classification system that evaluates food quality based on how much it has been transformed from its natural state through processing.

In food science, the structure or physical make up of food is referred to as the food matrix. Every ingredient and processing method contributes to a food item’s structure and therefore influences how it is digested and metabolized in the human body.

What is unique about the Siga food labeling approach is that it focuses on the manufacturing process as opposed to the nutritional composition, which is what most ranking systems rely on to rate the quality of a food item.

“Siga built a methodology to assess food according to its degree of processing,” CEO Aris Christodoulou told Xtalks. “Historically, we have assessed food quality according to its nutrients then we reduce food into a sum of nutrients. That is not what we are doing with Siga; we look at the whole list of ingredients and we assess products according to processing made on these ingredients.”

In turn, the Siga approach is designed to encourage suppliers and manufacturers to improve food quality and help consumers pick products with the healthiest ingredients.

The system classifies a food product as “ultra-processed” if it has at least one ingredient that has been purified or denatured through a processing method such as cracking or chemical synthesis. The classification system identifies these ingredients as “ultra-transformation markers” because they transform the food matrix from its natural structure and negatively alter the health potential in comparison to its original ingredients.

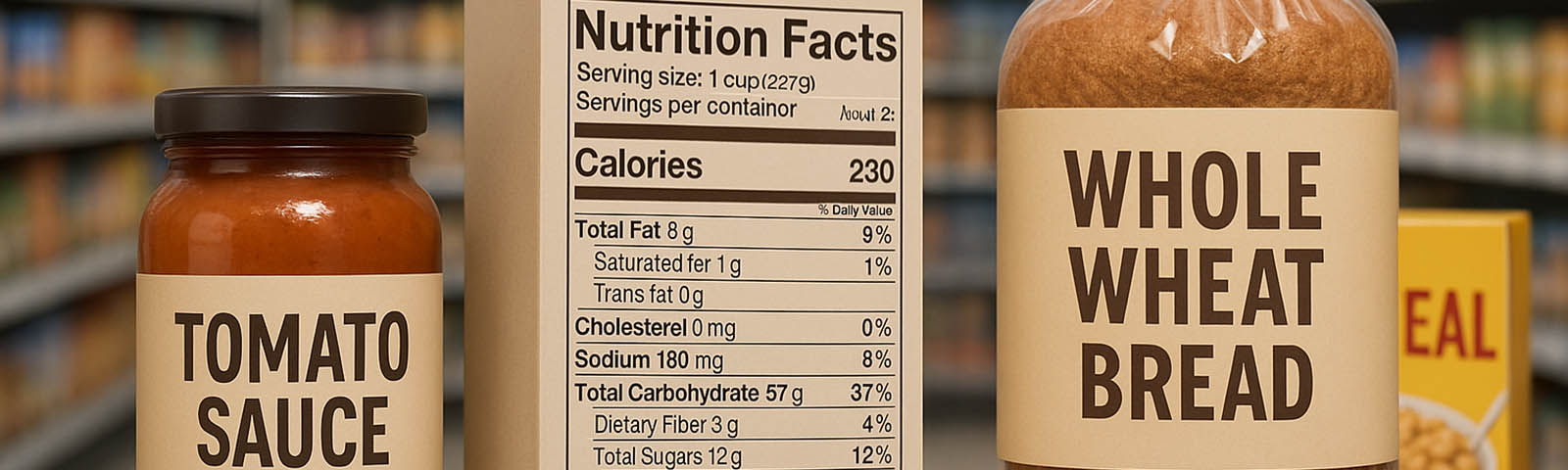

To depict how processed a food item is, the company analyzes the ingredient list and nutrition label and then calculates how processed the food items are by examining virtually all its ingredients, including additives.

“Is there evaporated sugar, refined sugar or hydrolyzed sugar?” asks Christodoulou. “Is there virgin oil, refined oil, or hydrogenated oil? These are not the same processes and not the same qualities.”

It then uses scientific opinion backed by health agencies like the World Health Organization to measure potential risks associated with these ingredients. It also uses data from the UK’s Food Safety Standards to asses how salt, fat, and sugar affect the “nutritional threshold” of a product.

After analyzing the data, Siga uses numbers, letters, and colors to categorize each food product from unprocessed to ultra-processed and gives medals to food items that contain the most natural list of ingredients.

This categorization method makes it similar to the French NutriScore system in the sense that it uses colors and letters to classify food by its quality. However, where this unique system differs is its ability to provide a detailed evaluation of which ingredients are processed as well as the health and safety concerns associated with food additives. It also provides manufacturers with recommendations on how to improve and reformulate their products.

“When we work with manufacturers, we look at their offer and we compare it to the market and provide them with insights on the ingredients they use against the market. They can use that information to improve their recipes or to promote their good quality policies to retailers or directly to consumers,” says Christodoulou.

According to Christodoulou, the current NutriScore system in France doesn’t evaluate how processing affects the quality of the food products it examines. Instead, it uses a “reductionist” method that measures a food item’s quality based on “positive” and “negative” attributes. For example, sugar has a negative score and fiber has a positive score in its classification system.

Christodoulou further states this method prohibits consumers from being able to distinguish food items that are “simply processed” from “ultra-processed.” Christodoulou also says processed foods are more prominent in North America and the UK and the problem is reaching other parts of the globe as well.

“We estimate that more than 80 percent of the food found in your supermarkets are ultra-processed. If that’s true, there are more ultra-processed foods within the UK, USA and Canada, and the problem is now in developing countries too such as Brazil and India,” Christodoulou said.

As industrial food systems and advancements in food-tech grow in popularity, packaged, branded and ready-to-eat foods are dominating the grocery aisles and the diets of many consumers. With this in mind, a food labeling system that brings awareness to consumers as well as provides manufacturers with better insight on how to reformulate products could help combat the future incidence of conditions such as obesity, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

*Editor’s Note: This article has been updated from August 21st, 2019 to include original quotes.

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN