Researchers at McGovern Medical School at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, have identified a genetic mutation in the THSD1 gene which has been associated with intracranial aneurysms. The same mutation that was identified in patients – the details of which were published in the journal, Stroke – was further studied in two animal models of brain bleeding.

Using whole exome sequencing, the researchers studied over 500 participants, many of whom had a family history of sudden intracranial aneurysms. From this analysis, they pinpointed the THSD1 gene, which is predicted to cause cerebral arteries to form weak areas when the gene is mutated.

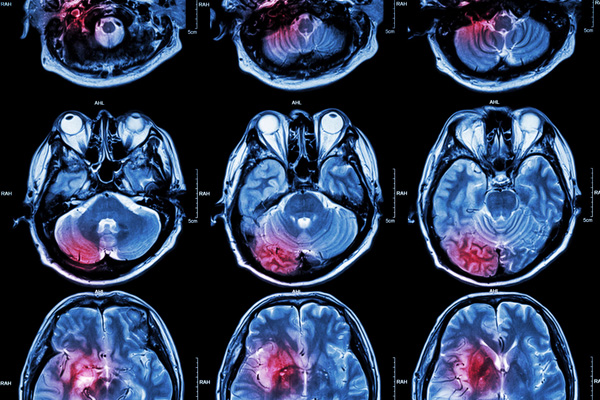

When artery walls in the brain are compromised, the pressure of the bloodstream could cause the vessels to rupture. Blood from the ruptured artery can fill the subarachnoid space between the brain and surrounding tissue, leading to disability or death.

The researchers further studied the gene mutation by inducing a loss-of-function of the THSD1 gene in genetically modified zebrafish and mice. Both animal models – commonly used to model human diseases – showed cerebral hemorrhage and higher rates of mortality when the THSD1 gene was nonfunctional.

“We have known for quite a while that aneurysms can run in families, so we knew there had to be a genetic variant responsible, but it took several years of painstaking genetic detective work to get to the point where we could identify this specific mutation,” said Dr. Dong Kim, director of Memorial Hermann Mischer Neuroscience Institute at the Texas Medical Center, and the senior author on the publication. “The clue that unlocked this mystery came from sequencing the genome of a specific large family in which multiple members had suffered brain aneurysms, and the evidence linking THSD1 to this disease began to build from there. It’s truly a fascinating discovery because, prior to this research, hardly anyone knew what this gene did or how it worked.”

According to Kim, the combined evidence suggests that the THSD1 mutation prevents epithelial cells from adhering to the extracellular matrix along the inner wall of cerebral arteries. Because of this defect, blood flowing through the artery slowly weakens the vessel wall, leading to bulges that have the potential to burst.

“As blood continues to rush through that artery, it bulges more and more, until at some point it can rupture,” said Kim. “By identifying the role this high-risk genetic variant of THSD1 plays in leading to the formation of intracranial aneurysm, we now have a better grasp from a molecular level of why aneurysms occur. This research serves as a solid foundation on which to continue building our scientific understanding of a disease that, until now, has been somewhat of a genetic enigma.”

Around 30,000 people in the US suffer a subarachnoid hemorrhage every year, with a prevalence of about 3 percent of the general population. Of these cases, approximately 40 percent will result in death, with the remaining patients facing profound neurological impairments.

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN