After studying the first birth cohort in Denmark to be offered the HPV vaccine, researchers at the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences at the University of Copenhagen have concluded that the vaccine works to reduce the growth of abnormal cells – known as dysplasia – which could eventually lead to the development of cervical cancer. The study – which was published in the International Journal of Cancer – is the first of its kind to study the impact of the HPV vaccine on the general population.

Fifteen of the over 100 different types of Human Papilloma Virus have been associated with the development of cancer. In 2017, a new version of the HPV vaccine – Gardasil-9 – which could prevent up to 90 percent of all new cases of cervical cancer was introduced in Denmark. While this vaccine protects against more HPV strains than its earlier iteration (Gardasil-4), both shots are effective against HPV 16 and HPV 18 which are responsible for 70 percent of all cases of cervical cancer.

“It is the first study in the world to test the Gardasil-4 vaccine on a population level,” said Professor Elsebeth Lynge, of the Department of Public Health, University of Copenhagen and senior author on the study. “The childhood vaccination programme, which includes the HPV vaccine, is targeted at the entire population. Therefore, it is important to look at the entire population and the effect of the vaccine after the first screening of women aged 23 years.”

In 2009, the HPV vaccine officially became part of the Danish childhood vaccination programme, with girls born in 1993 being the first to receive the vaccine. It was this cohort of women that was studied by the Danish researchers and compared to a cohort of girls born 10 years earlier – in 1983 – who were not offered the HPV vaccine. In an attempt to control for other variables, the researchers established that the two birth cohorts were comparable in a number of ways from level of education achieved, to average age of first sexual experience.

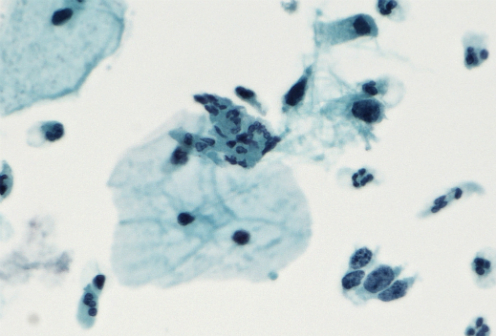

The women’s first cervical screening tests were compared to determine whether receiving the vaccine had an effect on their reproductive health. The women born in 1993 underwent their first cervical screening test in 2016, while those born in 1983 had the test in 2006.

The researchers found that women belonging to the 1993 birth cohort showed a 40 percent reduction in the risk of severe dysplasia compared to the 1983 cohort. According to the researchers, the 1993 birth cohort received their HPV vaccination at 15 years of age, and that since today’s girls are given the vaccine when they are 12, they could have an even more positive response to the immunization.

“This means that fewer women have to be referred to a gynaecologist for further examination and have a tissue sample taken. Eventually we also expect fewer to fall ill,” said Lise Thamsborg, first author of the study. “It is better. We expect the effect to be greater among those vaccinated at the age of 12, because very few have been sexually active at this age.”

Perhaps counterintuitively, the women belonging to the 1993 cohort showed higher levels of mild dysplasia compared to their 1983 counterparts. However, the researchers explain that this result could be explained by the introduction of new technology in 2006 which was better at identifying dysplasia in cell samples.

“The new technology has led to fewer inadequate samples, and the samples are of a higher quality today” said Thamsborg. “So, the samples are more sensitive. This may be the cause.”

The researchers plan to conduct further studies on samples collected from women with dysplasia to further understand the development of abnormal cells. But for now, the findings suggest that the HPV vaccination program is working and women are being protected from infection which could later lead to the development of cervical cancer.

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN