According to a new study published in the journal Pediatrics, only 18 percent of US children with sick cell anemia are receiving a crucial medication to prevent infections associated with the inherited blood disease. The researchers say that bacterial infections are much more common in those with sickle cell disease, and that antibiotics can reduce this risk by 84 percent.

“Most children with sickle cell anemia are not getting the antibiotics they should be to adequately protect against potentially deadly infections,” said lead author Dr. Sarah Reeves, pediatrics faculty and epidemiologist with the Child Health Evaluation and Research Center at the University of Michigan Medical School and C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital. “Longstanding recommendations say children with sickle cell anemia should take antibiotics daily for their first five years of life. It can be lifesaving.”

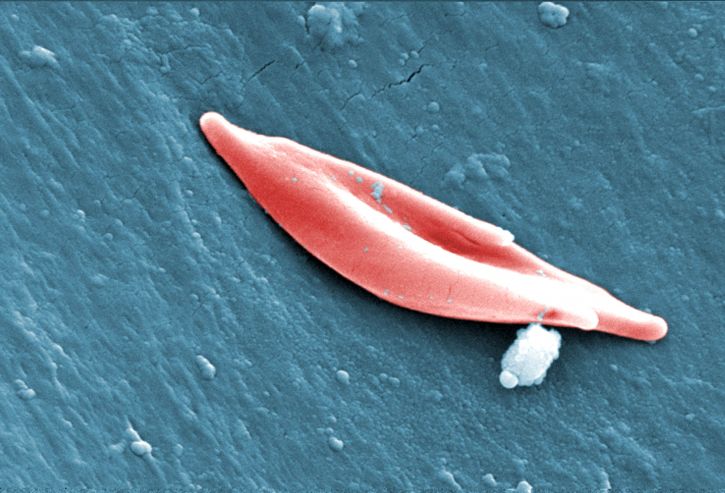

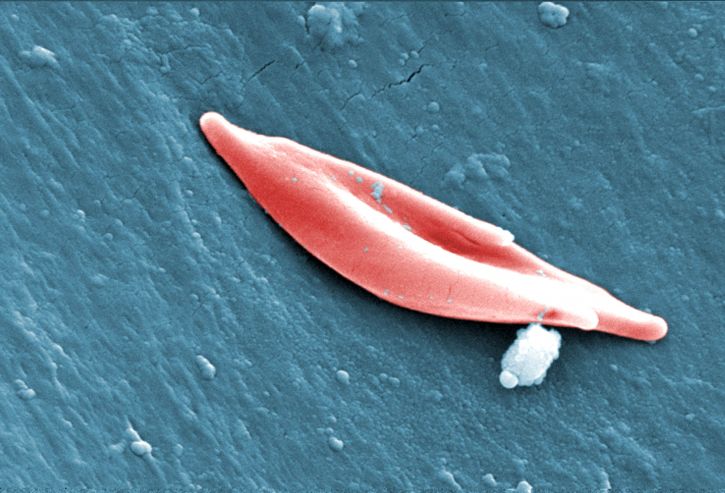

Sickle cell anemia is a disease which distorts the shape of red blood cells, affecting their oxygen carrying capacity, and is the most common inherited blood disorder. The African-American population is most affected by the disease, of which 1 in every 375 children is diagnosed.

Diagnosis with sickle cell anemia puts children at a 100-fold increased risk of developing bacterial infections, compared to healthy children. If left untreated, infections can become complicated resulting in meningitis and even death. Prophylactic antibiotic use is the first line of defence against these potentially life-threatening infections for children with sickle cell anemia.

In order to assess the use of these important antibiotics, Reeves and her colleagues studied 2,821 sickle cell anemia patients between the ages of three months and five years. The study took place between 2005 and 2012, and patients included in the study lived in five US states: Florida, Illinois, Louisiana, Michigan, South Carolina and Texas. Insurance claims data was used to determine whether the patients’ prescriptions for antibiotics were filled by a pharmacy.

They found that less than 20 percent of pediatric patients with sickle cell anemia were taking their antibiotic medications. Given this startling statistic, the research team sought to identify some of the barriers to medication adherence in this patient population.

According to Reeves, one of the potential barriers is the regularity with which caregivers must pick up the antibiotic medications from a pharmacy. Prescriptions are usually refilled every two weeks.

Another factor relates to administering the medicine to a child on a regular dosing schedule. Since children with sickle cell anemia can outwardly appear to be fine and heathy, it may be difficult for caregivers to remember to give them the antibiotic medication twice a day.

“The types of challenges involved in making sure children get the recommended dose of antibiotics is exacerbated by the substantial burden of care already experienced by families to help control the symptoms of this disease,” said Reeves. “Interventions to improve the receipt of antibiotics among children with sickle cell anemia should include enhanced collaboration between health care providers, pharmacists and families.”

Reeves says it may be helpful to implement an alert system which reminds doctors that antibiotics need to be prescribed and caregivers need to be informed of the importance of regular dosing. However, she admits that future studies will need to explore this topic further to fully identify what’s keeping medication adherence numbers so low.

“Doctors need to repeatedly discuss the importance of taking antibiotics with families of children with sickle cell anemia,” said Reeves. “Social factors that may impact receiving filled prescriptions should also be considered, such as the availability of transportation and time to travel to pharmacies to pick up the prescriptions.”

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN