Researchers at the Cincinnati Children’s Center for Stem Cell and Organoid Medicine (CuSTOM) and Yokohama City University in Japan have designed a mass production system for liver tissue suitable for transplant into human patients. The team published the details of their bioengineering platform in the journal Cell Reports.

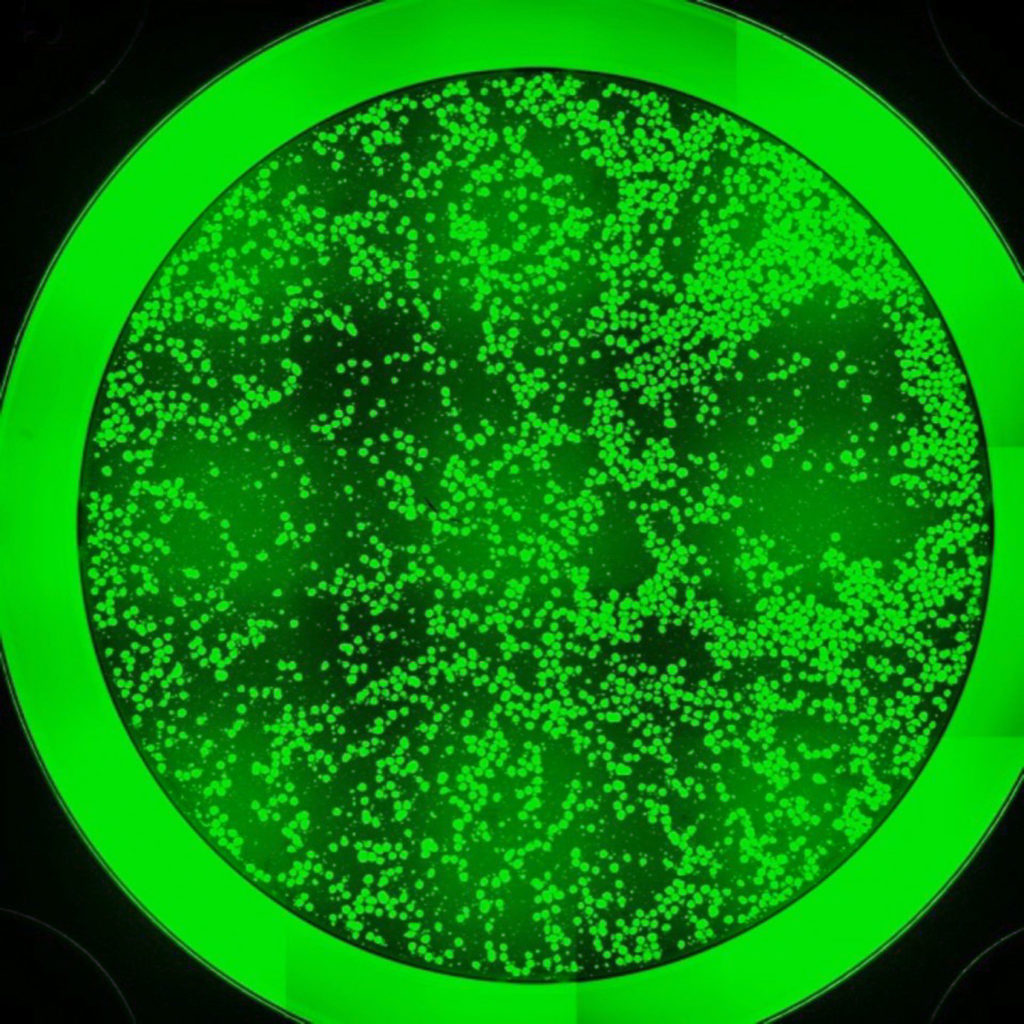

The research team has overcome some of the most challenging aspects of large-scale synthesis of biological tissue to create a process capable of generating as many as 20,000 genetically compatible liver micro-buds at one time. When the micro-buds are combined, they are composed of enough liver cells to be transplanted into a patient with liver failure.

Best of all, the human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) were grown without the need for animal byproducts – such as bovine serum albumin – which would otherwise prevent them from being used for therapeutic purposes. The researchers point out that the bioengineered liver tissue could also be used in research, including in testing new hepatological drugs.

In generating the liver buds, the researchers first collected iPSCs from donors to grow three essential types of liver cells: hepatic endoderm cells, endothelial mesenchyme cells and septum mesenchyme cells. These cells were then transferred to custom-designed, U-shaped micro-wells coated with a special film designed to support the growth and development of the hepatocytes.

The separate cell types then formed organized, three-dimensional micro-buds which function like native liver tissue. When these liver micro-buds were collectively transplanted in mouse models of liver disease, the researchers found they were able to compensate for the lack of liver function.

“Because we can now overcome these obstacles to generate highly functional, three-dimensional liver buds, our production process comes very close to complying with clinical-grade standards,” said Takebe. “The ability to do this will eventually allow us to help many people with final-stage liver disease. We want to save the lives of children who need liver transplants by overcoming the shortage of donor livers available for this.”

According to Takebe, clinical trials of the lab-grown liver tissue could begin in the next two to five years. Until then, the researchers will continue to improve the technique.

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN