Our appetite for new obesity treatments will never be satiated – and for good reason. Obesity affected nearly 93.3 million US adults between 2015 and 2016, accounting for almost 30 percent of the total population at the time. Obesity increases the risk for cardiovascular disease, diabetes and hypertension.

From diet pills to gastric bypass surgery, there are a plethora of ways to reduce food intake or make individuals feel fuller. Medical devices also play a role in helping with weight loss.

According to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), devices known as electrical stimulation systems block neurotransmission between the brain and the stomach. One such device, called the Maestro Rechargeable System, involves an external pulse generator which sends signals to electrodes implanted near the vagus nerve in the abdomen. Among its many functions, the vagus nerve stimulates muscle contractions to empty the stomach during digestion. The FDA approved Maestro for commercial use in 2015.

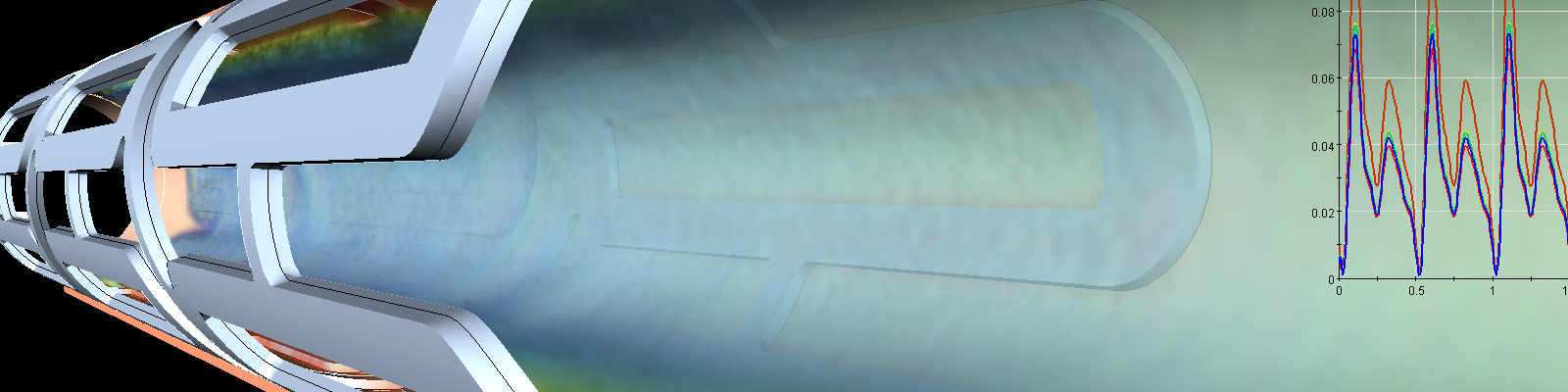

Engineers led by Dr. Xudong Wang at the University of Wisconsin-Madison developed a next-generation, implantable weight loss device. The 1cm-long device can send electrical signals to the vagus nerve through pulses of the stomach walls. That is, the “stomach power” and not a battery, is driving vagus nerve blockade.

“It’s automatically responsive to our body function, producing stimulation when needed,” said Wang. “Our body knows best.”

The battery-operated Maestro could be cumbersome especially if the user must charge the battery frequently. In an article published in Nature Communications, the team demonstrates the safety and efficacy of the device when implanted in rats.

They found that rats implanted with the device for 15 days consumed only two-thirds the amount of food consumed by rats in the control groups. At the end of the 100-day study, the rats implanted with the device experienced a 35 percent weight loss within 2.5 weeks, and were able to recover their normal weight pattern after the device was removed.

The ability to reverse the effects of the device is an attractive feature. But practically speaking, how would this work for someone who has had the device surgically implanted into their stomach? Perhaps the researchers can learn from the team at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who developed a wirelessly-controlled pill that can lodge into the stomach wall with expandable arms.

While the researchers did not report any toxicity or signs of inflammation from the device, it’s hard to predict how the device will tolerate the highly acidic environment of a human stomach over a long period of time. The researchers’ next step is to test their device in larger animal models.

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN