Researchers at UT Southwestern Medical center have precisely edited the bacterial species that colonize the gut of mice to treat the inflammatory bowel disease known as colitis. According to the study team – who published their findings in the journal Nature – their technique targeted microbes with metabolic pathways associated with intestinal inflammation.

“Our results provide a conceptual framework for precisely altering the bacterial species that line the gut in order to reduce the inflammation associated with the uncontrolled proliferation of bacteria seen in colitis and other forms of inflammatory bowel disease,” said Dr. Sebastian Winter, Assistant Professor of Microbiology at UT Southwestern. “We stress that this is a proof-of-concept study in which a form of tungsten, a heavy metal that is dangerous in high doses, was used. It is never safe to ingest heavy metals. Now that we have a drug target [the bacterial pathway], our goal is to find a safe therapy that exerts a similar effect.”

While researchers have long known that microbial species in the intestine have an effect on the overall health of the gut, and can even contribute to the development of inflammatory bowel diseases like colitis, studying these species individually is no easy feat. The diversity of species that comprise the gut microbiome make it difficult to pinpoint exactly which types are beneficial and which are disease-causing, and each person carries a different mix of microbes.

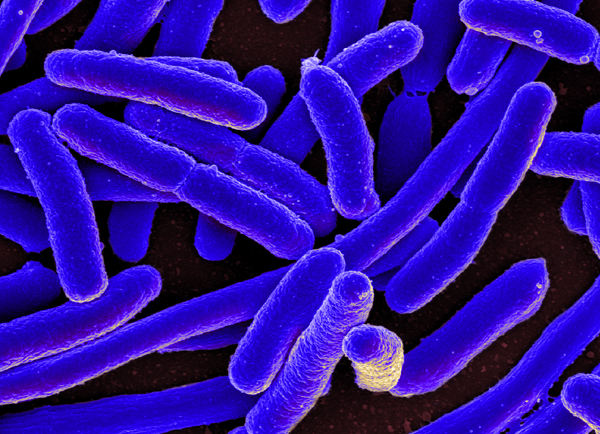

Nonpathogenic E. coli is one bacterial species which plays a double role. When present in small numbers, the bacteria can offer a protective effect against pathogenic species such as Salmonella; when E. coli bacteria over-colonize the gut, however, the imbalance can contribute to development of inflammatory bowel disease.

Previous research conducted by Winter and his team found that E. coli and other members of the Enterobacteriaceae family make use of specialized metabolic pathways to generate cellular energy and support overgrowth. These strategies help the bacterial species out compete beneficial bacteria.

“These pathways are unique in the sense that they are only present in certain bacteria and only function during gut inflammation,” said Winter. “That situation presented an opportunity for rational design of prevention and treatment strategies for conditions related to gut inflammation, such as IBD.”

This finding led the team to test a form of tungsten to impede the growth of E. coli. They found that by adding the heavy metal to the mice’s drinking water, they were able to selectively prevent the overgrowth of the harmful bacteria, without affecting any beneficial strains. By addressing the imbalance, the researchers found that the overall health of the mice was also improved.

“It is worth noting that our strategy only inhibits the bloom of Enterobacteriaceae during intestinal inflammation without getting rid of them entirely. This finding is important because in the proper ratios, Enterobacteriaceae also fulfill the role of resisting colonization by bacterial pathogens,” said Winter. “Therefore, controlling the bloom of these bacteria during episodes of inflammation is preferable to removing them from the system completely.”

But since Tungsten can have negative neurological and reproductive effects on humans, the researchers say a safer therapeutic will need to be developed to target this molecular pathway.

“In our case, we found a way to target only one family of bacteria, the Enterobacteriaceae, and only during inflammation,” said Winter. “More study is needed to find potential therapies for human disease, but this is a promising first step.”

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN