Findings published in Nature Immunology, on Monday, show potential in using our body’s immune system to treat all cancers. Researchers from Cardiff University have found a way of killing cancers that range from prostate, lung and breast in lab tests.

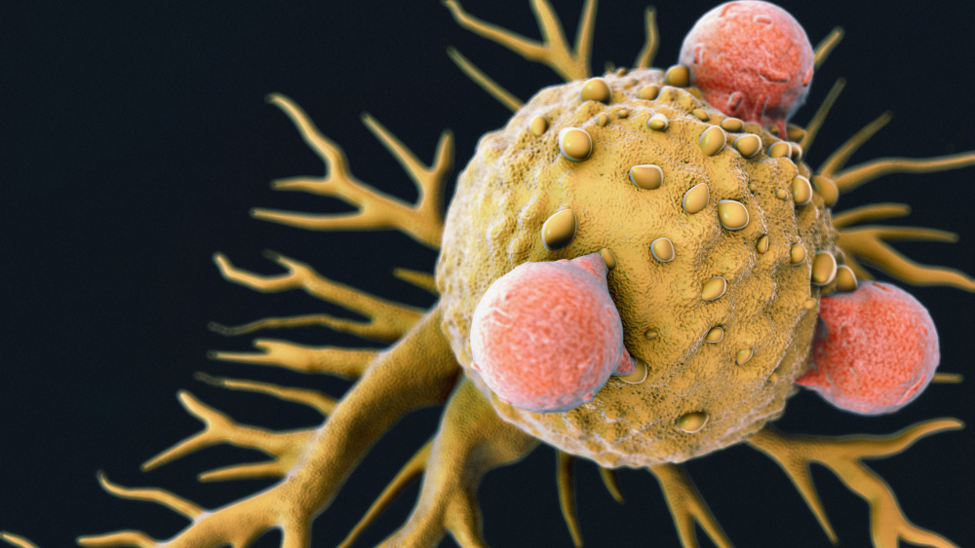

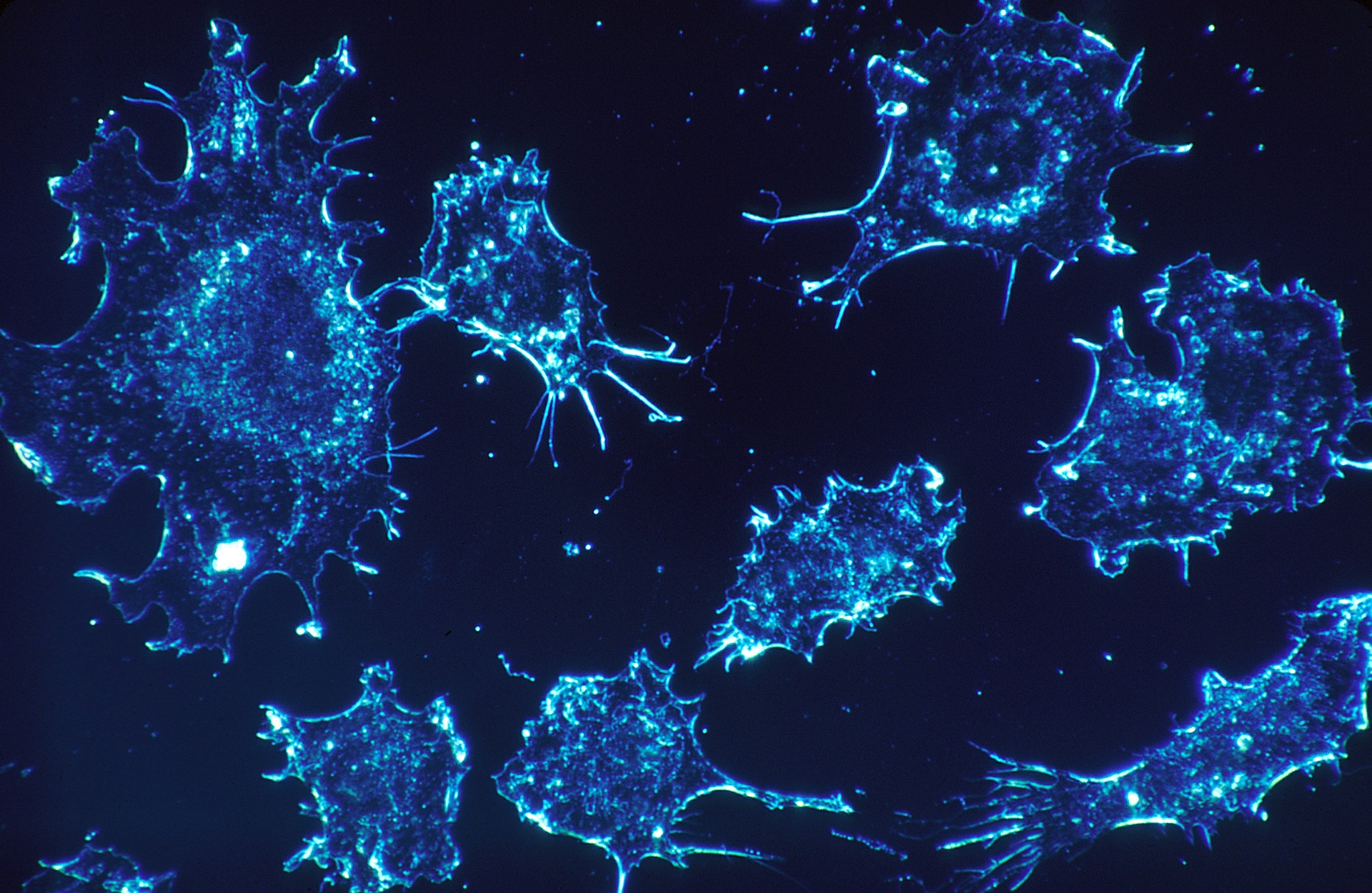

Scientists were looking for different ways that our immune system reacts to tumors or cancer cells. They then recognized a T-cell in people’s blood that could provide a way to fight the cells. This T-cell is an immune cell that aids the body in scanning whether there is a threat that needs to be defeated. The difference is that this T-cell could help attack a wide range of cancers as opposed to a single tumor type.

Andrew Sewell, lead author on the study and an expert in T-cells from Cardiff University’s School of Medicine, told BBC that “there’s a chance here to treat every patient…nobody believed this could be possible.”

Although they are still in the early stages of the research, experts say this is very exciting.

Outstanding and exciting cancer research is happening across Cardiff University: https://t.co/FO6ozEdDZJ pic.twitter.com/FFp3Be5UPC

— Research Institute (@CUCancerInst) January 21, 2020

Sewell later added, “it raises the prospect of a ‘one-size-fits-all’ cancer treatment, a single type of T-cell that could be capable of destroying many different types of cancers across the population.”

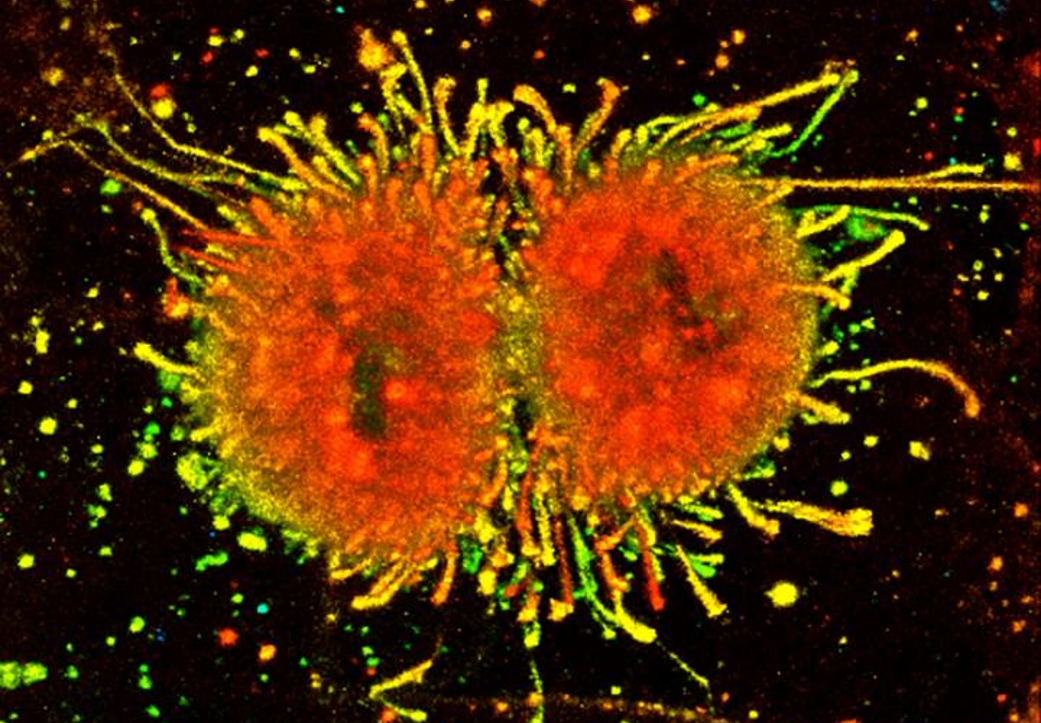

T-cells are a type of white blood cells called lymphocytes that play an important part in fighting infection and disease. T-cells move around the body to detect and destroy cells. When it comes in contact with a new infection, the body makes T-cells that are specific to the infection and fight it. The T-cells retain a memory of the foreign cell in case the body were to come across that infection again, allowing the body to recognize the disease and attack it immediately.

The T-cell that the researchers discovered is a bit different in the sense that it is equipped with receptors that can identify different cancer types through a single cell- surface protein called MR1. Usually, when T-cells scan for abnormalities they recognize small parts of cellular proteins attached to cell-surface molecules called human leukocyte antigen (HLA). The HLA varies between individuals, which makes it difficult for scientists to create a single T-cell based treatment. However, unlike HLA, MR1 does not vary in the human population, making the treatment a “one sit fits all.”

CAR-T cell therapy is a type of immunotherapy where scientists collect and make changes to T-cells that then target the cancer cells. To test the T-cell receptor for the MR1, researchers injected the T-cell receptor into mice bearing human cancer with a human immune system. “This showed ‘encouraging’ cancer-clearing results which the researchers said was comparable to the now NHS-approved CAR-T therapy in a similar animal model.”

Sewell, said “it was ‘highly unusual’ to find a T-cell receptor with such broad cancer specificity and this raised the prospect of ‘universal’ cancer therapy.’”

The research is in the early stages, but experiments are underway in order to determine the precise mechanism in which the T-cell receptor differentiates between healthy and cancer cells.

The Cardiff Group hope to begin trials for this new approach in patients towards the end of the year. They also aim to perform ongoing safety testing to make sure that modified T-cells with the T-cell receptors only recognize cancer cells.

“There are plenty of hurdles to overcome however if this testing is successful, then I would hope this new treatment could be in use in patients in a few years’ time,” Sewell said.

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN