When operating on a patient with cancer, surgeons don’t always have the ability to clearly see which tissue is healthy and which is malignant. To help identify cancerous lymph nodes, surgeons at Penn Medicine are leading a trial to see whether a fluorescent dye can be a better way to identify diseased tissue during surgery.

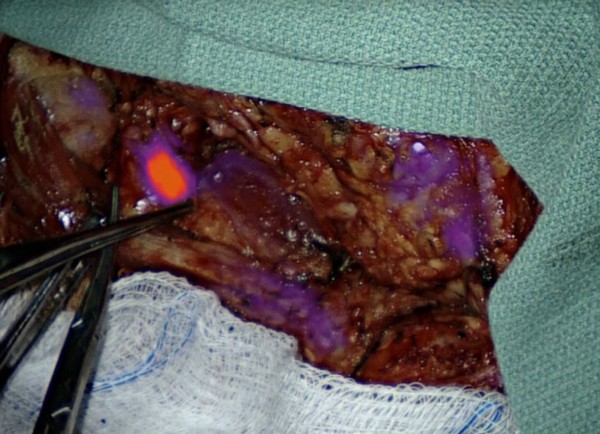

The dye preferentially binds to cancer cells, effectively “lighting up” the areas that must be resected during surgery to remove head and neck tumors. The current study is the first to focus on applying this– known as intraoperative molecular imaging (IMI) – to lymph nodes.

Head and neck cancers account for approximately four percent of all cases of the disease in the US, which can affect different tissue types, such as the mouth or the sinuses. This year, over 65,000 individuals in the US will be diagnosed with the form of cancer. The majority of head and neck cancers as associated with tobacco and alcohol use, however they have also been linked to infection with human papillomavirus (HPV).

Lymph nodes act as a filter for the immune system, however they also provide head and neck cancers with a means to metastasize throughout the body. As surgeons are often unable to determine whether lymph tissue contains these malignant cells, they may remove healthy tissue in an effort to be thorough, or leave small numbers of cancer cells behind which can act as seeds for recurrence.

“By using a dye that makes cancerous cells glow, we get real time information about which lymph nodes are potentially dangerous and which ones we can leave alone,” said Dr. Jason G. Newman, an associate professor of Otorhinolaryngology in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. “That not only helps us remove more cancer from our patients during surgery, it also improves our ability to spare healthy tissue.”

The contrast agent – known as indocyanine green (ICG) – has been used by others to visualize lung and brain cancer during surgery, however the current study is the first to test its effectiveness on lymph tissue. Originally designed to help physicians view blood flow in patients, the fluorescent dye already has FDA approval.

“We know that tumors hold onto this dye longer than most other tissues, so if it is administered to a patient several hours before surgery, the tumors will still glow long after it has disappeared from the rest of the body,” said Newman.

While Newman and his colleagues are currently testing ICG, he says that other available dyes may be more appropriate for visualizing disease lymph tissue. By studying tissue tagged with the fluorescent dye, oncologists may be better equipped to make predictions on the likelihood that a patient’s cancer will return.

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN