A new study conducted by researchers at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health has revealed that infection with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) could cause multiple sclerosis (MS).

The study was published in the journal Science this month.

The study found that EBV infection could lead to a 32-fold greater risk of developing MS. The researchers made it clear, however, that a definite link still cannot be established.

EBV is a type of herpes virus that typically causes infectious mononucleosis, which is readily transmissible through saliva. The virus does not clear from the body and instead, becomes latent in the host, remaining dormant until a stimulus may trigger its reactivation.

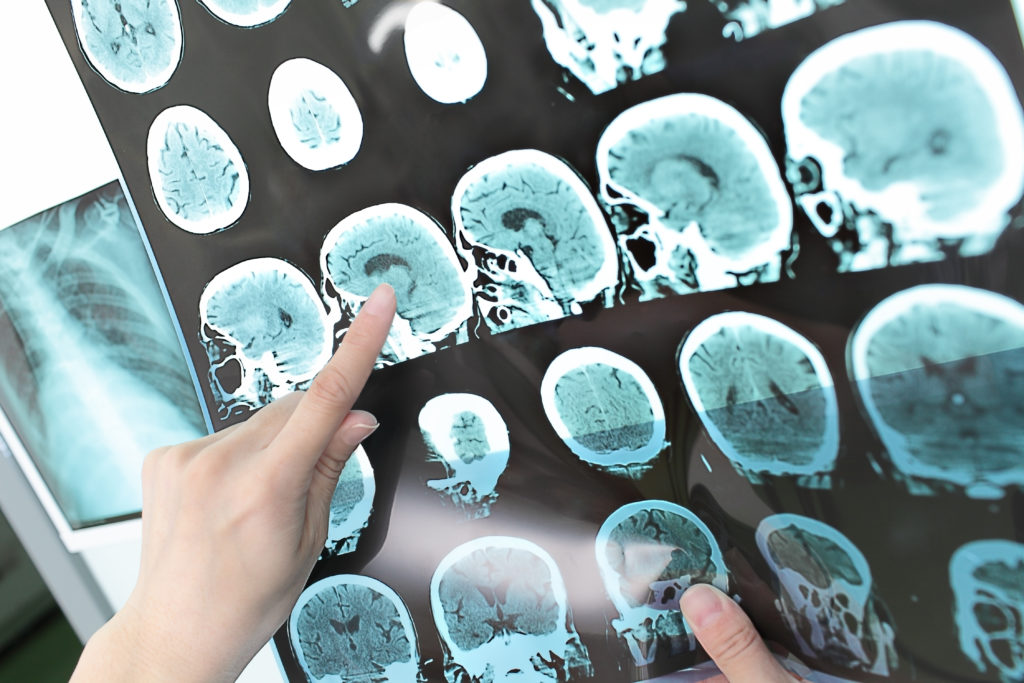

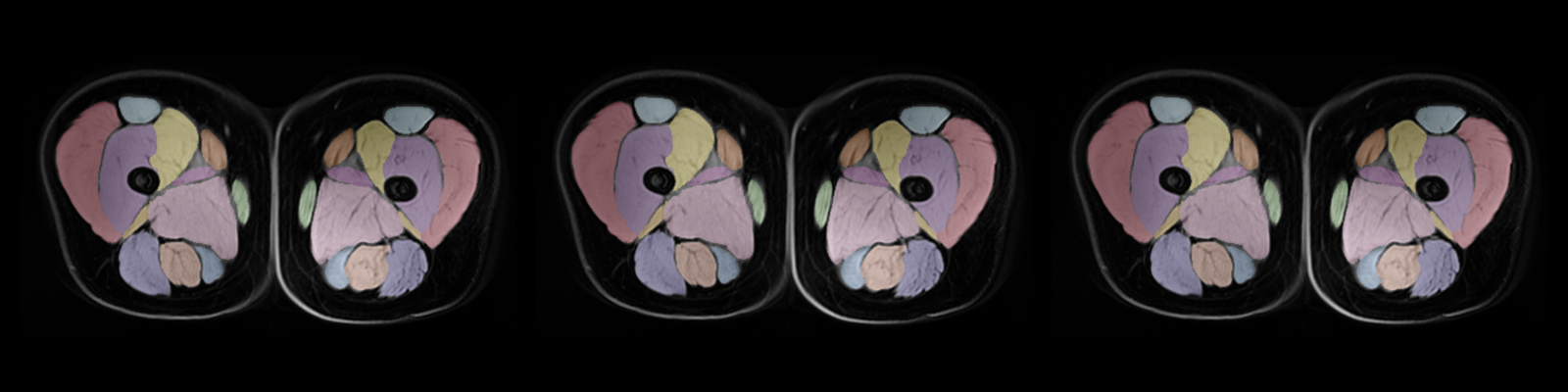

MS is a chronic inflammatory, demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS) in which the myelin sheaths of neurons in the brain become damaged. This impairs the transmission of signals between the nerve cells, leading to various neurological symptoms, including motor deficits like coordination problems due to muscle weakness, vision problems, numbness and pain.

Approximately 1 million people are currently living with MS in the US.

About 95 percent of adults carry EBV and most people are infected with the virus in childhood. This has made it difficult to ascertain its link to diseases like MS because symptoms of the disease typically appear about ten years after EBV infection.

According to the Multiple Sclerosis Association of America (MSAA), people who live in temperate climates further from the equator have a greater risk of developing MS than people who live in either hotter areas near the equator or in significantly cold regions around the north or south poles. In addition, women are three times more likely to develop MS than men, indicating a possible role of hormones in the disease.

Related: Portable Neuromodulation Stimulator Gets FDA Authorization for MS Treatment

To investigate whether EBV causes MS, the Harvard research team conducted a longitudinal analysis in which they accessed 20 years’ worth of medical data for over 10 million young adults on active duty in the US military. The cohort consisted of a racially diverse pool of individuals. Of the service people, 955 were diagnosed with MS during their service period. Blood samples were available for 801 of these individuals among whom 800 tested positive for EBV.

The researchers analyzed the serum samples, which were collected every two years by the military. The research team tracked the development of MS and its relationship with EBV by looking at EBV status at the time of the first sample and the onset of MS during the period of active duty.

As part of the analysis, the researchers looked at a subset of 123 people who did not have MS nor EBV at initial blood sampling and divided them into two groups. The first group had 33 MS patients and contained 32 EBV-positive cases. The second was a control group of 90 people who did not have MS and had 51 EBV cases.

The analysis showed that the risk of MS increased 32-fold after infection with EBV; infection with other viruses like cytomegalovirus, which is transmitted in a similar manner to EBV, did not impact the risk. They also found that serum levels of neurofilament light chain, a biomarker of neuroaxonal degeneration typically seen in MS, increased only following EBV infection. The researchers concluded that the “findings cannot be explained by any known risk factor for MS and suggest EBV to be the leading cause of MS.”

“The hypothesis that EBV causes MS has been investigated by our group and others for several years, but this is the first study providing compelling evidence of causality,” said Alberto Ascherio, professor of epidemiology and nutrition at Harvard Chan School and senior author of the study in a press release from Harvard. “This is a big step because it suggests that most MS cases could be prevented by stopping EBV infection and that targeting EBV could lead to the discovery of a cure for MS.”

Anne Bruestle, an immunologist at Australian National University (ANU) who was not affiliated with the research, pointed out in an interview that while the data provides a rare, clear look at MS developing in association with EBV — a view that is normally challenging to attain because of the relatively small number of MS patients — all of the people in the 123-person cohort contracted EBV as adults. The implications of EBV infection in childhood versus adulthood are not known. However, EBV does present differently in children compared with adults, and adolescents and young adults may develop infectious mononucleosis. As a result, she said the conclusions of the Harvard study might not be applicable to those infected when very young.

According to Ascherio, the delay between EBV infection and the onset of MS may be in part due to symptoms going undetected during early stages of the disease and partially due to the evolving relationship between EBV and the host’s immune system, which is repeatedly stimulated whenever latent virus reactivates.

“Currently there is no way to effectively prevent or treat EBV infection, but an EBV vaccine or targeting the virus with EBV-specific antiviral drugs could ultimately prevent or cure MS,” said Ascherio.

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN