Researchers, pharmaceutical companies and clinical investigators are integral to drug discovery and development. However, clinical trials used to test the safety and efficacy of new drugs wouldn’t be possible without the contribution of one very important stakeholder: the human volunteers.

Every year, thousands of people volunteer to participate in clinical trials and test potentially life-saving drugs and therapies, as well as medical devices that could improve patients’ quality of life. Many of these individuals are known as “healthy volunteers”: people who have no known health problems who can be compared to patients with a specific disease or condition.

Oftentimes, these new drugs and devices are tested on healthy volunteers in early phase “first-in-man” clinical trials, before they are ever tested on the target patient population. As patients participating in clinical trials may need to stop taking other treatments to avoid confounding results, the use of these healthy volunteers prevents vulnerable patients from unnecessarily being exposed to experimental new treatments.

These Phase 1 clinical trials are primarily aimed at assessing the safety and tolerability of the drug at escalating doses. While investigational new drugs are normally tested first in healthy volunteers, in some cases, the patients themselves will act as test subjects. This is particularly true in cases where patients are terminally ill and they have few other treatment options.

Healthy volunteers cite various reasons for deciding to participate in clinical trials, which vary from person to person. Some people choose to volunteer based on purely altruistic motives and a desire to help advance medicine and our understanding of disease, while others may be driven to enroll based on economic factors and the promise of financial compensation.

Experiences in Clinical Trials

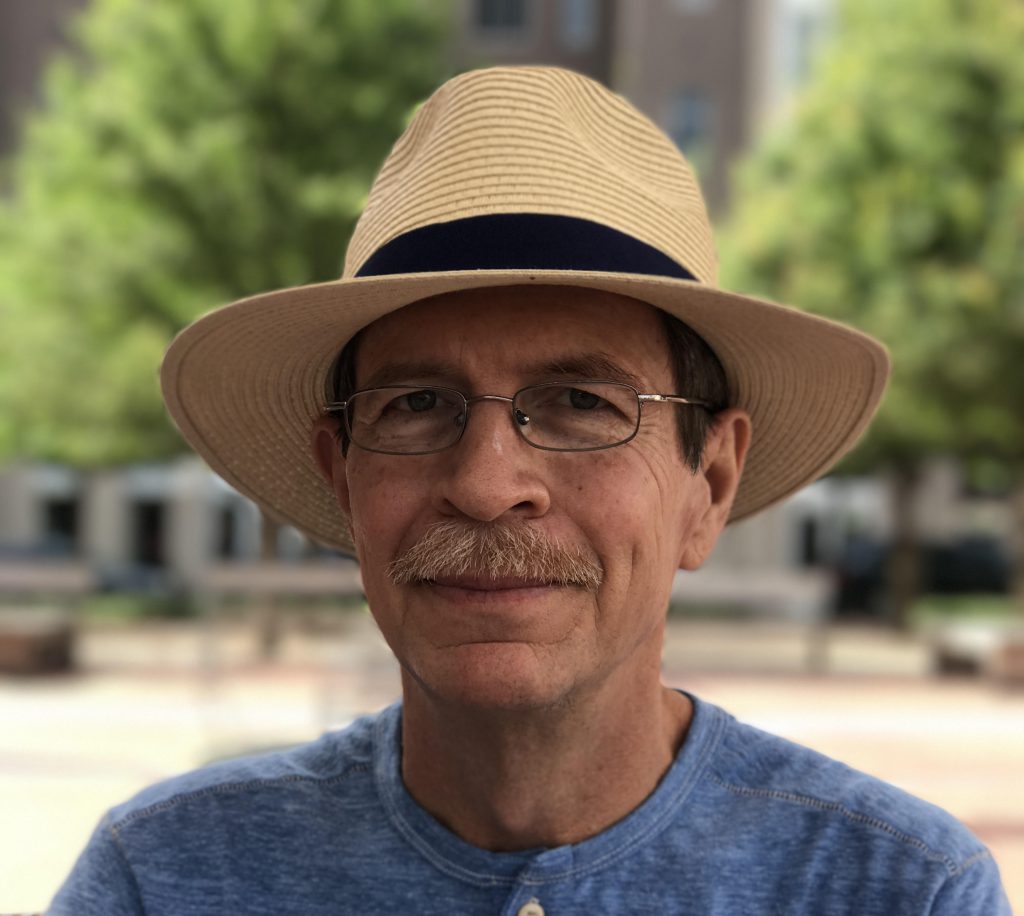

But for newly-diagnosed patients, the prospect of participating in a clinical trial takes on a whole new meaning. When John Rost was diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), a rare lung disease with no known cause characterized by extensive scarring of the tissue, he began to seek out clinical trials – specifically a Phase I trial in IPF – that could help him get faster access to promising new therapies.

“My diagnosis with IPF is what sparked my interest,” says Rost, now Chair of the Patient Advisory Board for monARC Bionetworks. “My dad had the same issue. He passed really quickly because he had a heart condition also.”

Approximately 100,000 Americans have IPF, with another 30,000 to 40,000 new diagnoses being made each year, according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Most individuals diagnosed with the lung disease survive for just three to five years.

By the time Rost was diagnosed with IPF, his lungs were functioning at less than 50 percent capacity. His scarring was progressively getting worse, so in 2015 he underwent a lung transplant. While the transplant was an effective treatment for IPF, it was not without its own risks; Rost must take immunosuppressant drugs for the rest of his life to prevent his body from rejecting the donor organ.

“At the time I was firmly diagnosed with IPF, I was too advanced to participate in the better, I guess you would call them, clinical trials – the ones that had the best chance of a positive outcome,” says Rost. “It would have been interesting to be part of the trial and it would have helped improve the knowledge base for IPF.”

After his transplant surgery, Rost launched a blog called The Primal Transplant to share his thoughts about life after the IPF diagnosis, and his experiences in maintaining his health through diet and exercise. The blog provided him with a way to connect with the IPF community and share the latest in IPF research, which he learned to understand and interpret by referring to a medical encyclopedia.

While Rost was precluded from participating in pharmaceutical trials, his interest in contributing to research and gaining a better understanding of the basis of his IPF drove him to explore non-drug trials. Before undergoing lung transplant surgery, Rost participated in an oxygen use study at National Jewish Health in Denver, Colorado, a hospital specializing in respiratory disease treatment and research. The purpose of the study was to see what effect supplemental oxygen had on a person’s activity level and quality of life, compared to baseline measurements taken before oxygen was prescribed.

As his lung transplant was successful, he participated in a biomarker trial looking to identify the hallmarks of patients at high-risk of chronic organ rejection. In addition, Rost has been a volunteer for two trials conducted at the University of Colorado and UT Southwestern which sought to uncover a genetic basis to familial forms of IPF. For Rost, the results of these trials were not what he was hoping for.

“It’s a little disappointing that they didn’t find anything to tie it genetically,” he explains, “so my children or grandchildren could get tested.”

Advice for Clinical Investigators

While Rost explains that his overall experience participating in clinical trials has been “neutral”, he admits that there’s room for improvement, particularly when it comes to post-study follow-up.

“Most trials don’t give any feedback,” says Rost. “You give them your blood, you fill out a lot of paperwork and that’s the last you hear of them.”

He says that the investigators running the genetics trial at the University of Colorado still send a newsletter from time-to-time to update past participants on general trends and the status of the trial. “A little thing like that, I would think, would go a long way to recruit for future trials,” he says.

Rost isn’t the only one with this opinion: a 2016 study published in the journal, Trials, found that 75 percent of clinical trial participants believe that study results should be disclosed to patients. However, sharing study results with participants is rare in clinical research, primarily due to a need to maintain the often-proprietary nature of the treatment under investigation.

Detailed results may only be shared publicly after data has been published, or a New Drug Application (NDA) has been submitted to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), or other regulatory body. Logistical challenges involving informing participants of study results can also prevent dissemination of information, as clinical trials often take years to be completed.

Rost also suggests that, wherever possible, clinical trial investigators expand the geographical reach of studies to provide more patients with the opportunity to participate. He points to the growth in remote, or virtual, clinical trials that don’t require patients to visit a central study site, but this trial design is often limited to a wearable device, and other non-drug clinical trials.

When asked what the term “patient-centricity” means to him, Rost is quick to say that it’s more than just an advertising slogan. A believer in the value of the patient voice, he says that patients have valuable insight into study design and could suggest strategies to promote communication within the study. This could also provide value for the study team and sponsor as successful patient retention can make or break a clinical trial.

In his role as Chair of the Patient Advisory Board for monARC Bionetworks, Rost is using his voice to directly contribute to the future of IPF trials. Specifically, the company – which develops digital research platforms for connected clinical trials – is focused on including more patients in trials through the use of a dedicated ResearchKit app. monARC has just launched their first trial in IPF.

“They are very interested in treatments and improving quality of life in pulmonary fibrosis,” says Rost. “They are looking for ways to better include patients and use devices in a trial so that patients in more rural areas can participate in trials without having to drive six or seven hours to the trial.”

Rost’s story is a reminder that a patient’s journey never really ends, particularly when it comes to rare diseases. But through clinical trial participation, writing about IPF and engaging with the larger patient community, Rost has found a way to turn his diagnosis into a way to bring about change and increase the patient-centric nature of these studies.

What changes are you seeing in patient involvement in clinical trials? Share your views in the comments section below!

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN