More isn’t always better, particularly when it comes to treating prostate cancer using radiation. A new study published in the journal JAMA Oncology has found that higher doses of radiation don’t improve survival time in patients with prostate cancer.

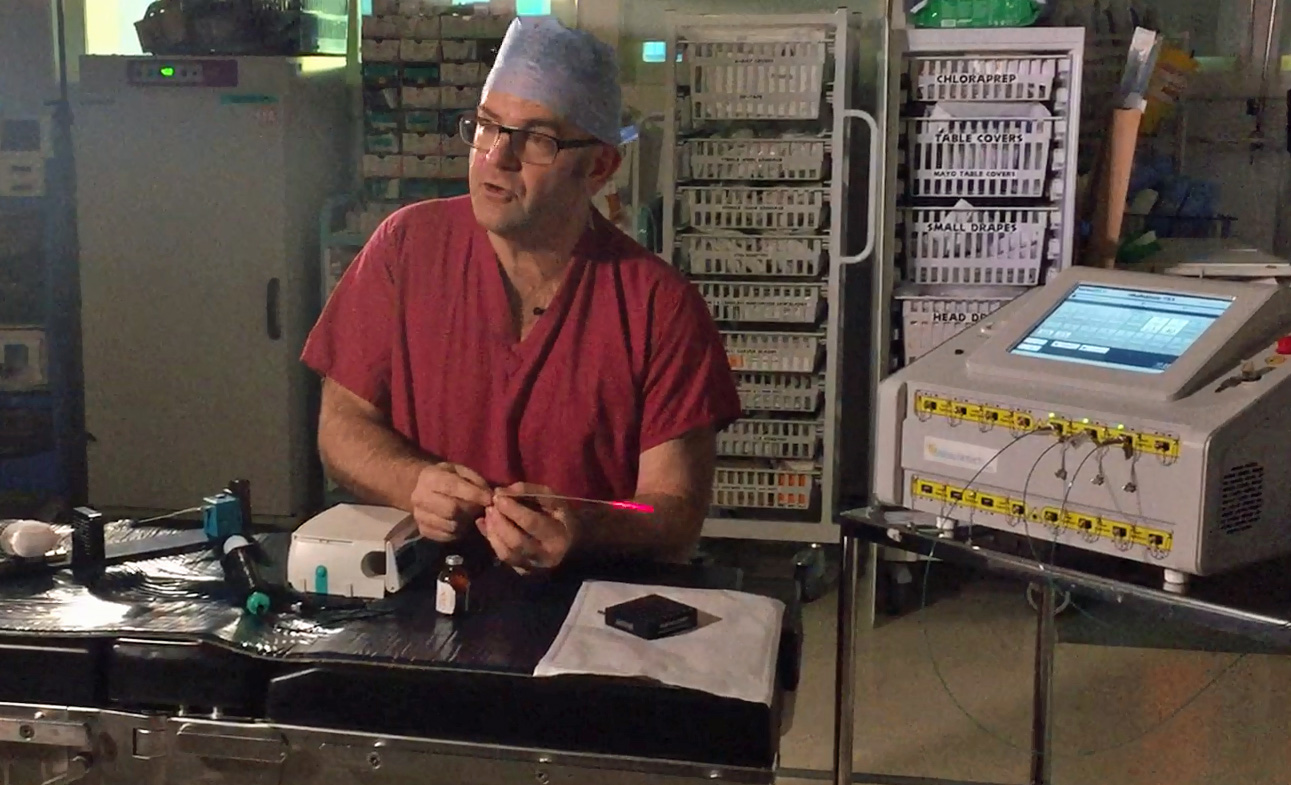

“Our goal is to improve survival, but we didn’t see that despite advances in modern radiotherapy,” said first author Dr. Jeff M. Michalski, the Carlos A. Perez Distinguished Professor of Radiation Oncology at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. “But we did see significantly lower rates of recurrence, tumor growth and metastatic disease—tumors that spread—in the group that received the higher radiation dose. Still, that didn’t translate into better survival. The patients in the trial did better than we anticipated, and part of that may have been because of improvements in metastatic cancer therapy over the 10 years of the trial.”

While previous research has found that increasing radiation doses over time can be useful in slowing tumor growth and improving other measures of cancer control, they did not examine patient outcomes. The new study included data from around 1,500 prostate cancer patients being cared for at over 100 radiation therapy oncology centers across North America, allowing Michalski and his colleagues to assess whether higher radiation doses had a measurable effect on patient survival.

About half the patients received increasing doses of radiation over the course of 44 visits up to 79.2 gray, while the other half received the standard dose of 70.2 gray in 39 treatment visits. After eight years of follow-up, 75 percent of the men receiving standard treatment were still alive, compared to 76 percent of those in the escalating dose treatment group.

While the difference in survival rates between the two groups was not statistically significant, patients receiving the standard treatment were more likely to need further treatment later on to control the cancer. In contrast, patients treated using the escalating doses of radiation experienced a higher rate of side effects.

“If there is a difference between standard and escalating doses, it’s hard to show it when the patients who later develop recurrent cancer can have their lives extended through the use of additional therapies,” said Michalski. “Of course, these additional therapies have their own side effects, as does the higher initial dose of radiation therapy. In addition, the selective use of androgen withdrawal therapy has been shown to improve survival in men treated with radiation therapy. This treatment can be combined with either standard or higher dose radiation therapy.”

According to Michalski, the availability of new therapies approved during the course of the follow-up period could have had an influence on the survival rates of those receiving the standard treatment. While he says that higher doses of radiation might not be right for every patient, it does have the benefit of reducing the risk of cancer recurrence.

“If we can safely deliver the higher dose of radiation, my opinion is to do that,” Michalski added. “It does show lower risk of recurrence, which results in better quality of life. But if we can’t achieve those ‘safe’ radiation dose goals, we shouldn’t put the patient at risk of serious side effects down the line by giving the higher dose. If we can’t spare the rectum or the bladder well enough, for example, we should probably back off the radiation dose. It’s important to develop treatment plans for each patient on a case-by-case basis.”

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN