Researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine say that the methods currently in use to measure levels of dormant HIV in patients, may be fatally flawed. According to the study investigators, many of the latent HIV proviruses – or those whose genetic information has been incorporated into the DNA of the infected host – are heavily mutated and are unlikely to be harmful.

Currently, HIV proviruses are quantified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to amplify certain HIV-specific genes. If most HIV genes are defective to the point of nonfunctioning, as the researchers have found, then this technique may be over estimating the number of latent viruses, which have the potential to reactivate and sicken the patient.

In order to come to their conclusions, the Johns Hopkins researchers sequenced the provirus genomes from 19 patients who were receiving treatment for HIV. In their analysis, they found that over 90 percent of the sequenced provirus contained a number of mutations which would render them nonfunctional.

Interestingly, the prevalence of defective proviruses was even identified in patients in very early stages of HIV infection, and those who were starting treatment right away. According to the researchers, their work – which was published in the journal, Nature Medicine – suggests that we must develop a new method to quantify the number of non-defective proviruses, as this is the number that could give patients and physicians an idea of how well certain HIV therapies are working.

“To cure HIV, you want to get rid of the proviruses without defects,” said Dr. Robert Siliciano, an infectious disease physician and molecular biologist at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and the senior author on the publication. “But our work shows that the standard assays used to do that are measuring forms of the virus that are not really relevant to these cure strategies.”

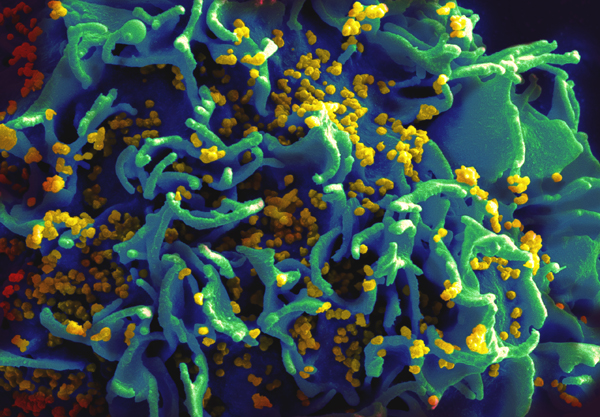

Antiretroviral therapies, which inhibit the virus from using the cell’s machinery to replicate, are the current standard of care for treating HIV infection. However, these drugs are unable to target the latent form of the virus, which lay dormant in certain types of cells within the immune system.

These proviruses can eventually reactivate, causing a recurrent infection in patients who may no longer be taking antiretroviral drugs. Siliciano, says that attempts to target these latent provirus reservoirs have so far proved unsuccessful.

Oftentimes when testing an experimental new HIV therapy, researchers measure levels of provirus reservoirs both before and after treatment, to gauge its effectiveness. Using PCR, the resulting provirus estimates include both virulent and defective HIV genes – a fact that wasn’t always considered to be a problem by researchers.

“Most of us in the field assumed that the initial pool of latent proviruses, immediately after infection, contained entirely functional copies of the virus, so we also assumed that PCR—at least for patients treated with antiretroviral therapy early in the course of infection—would mostly be counting proviruses that had the ability to cause disease again,” said Katherine Bruner, a graduate student in Siliciano’s laboratory, and the primary author on the paper. But Siliciano and colleagues’ results painted a different picture. “Even in patients treated really early, if you’re using a PCR-based approach to measure the reservoir, you’re really just detecting a lot of defective proviruses,” continued Bruner.

The researchers are hopeful that their results will help others better understand what the PCR technique is actually measuring. By knowing that those defective proviruses are found in large numbers early in the HIV infection, researchers will be able to account for this in their evaluation of new therapies.

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN