Patients with a chronic disease often struggle to keep up with the numerous pills or intravenous injections required to manage their condition. Now, researchers at the University of British Columbia (UBC) have developed Canada’s first magnetic drug implant as an alternative mode of drug delivery.

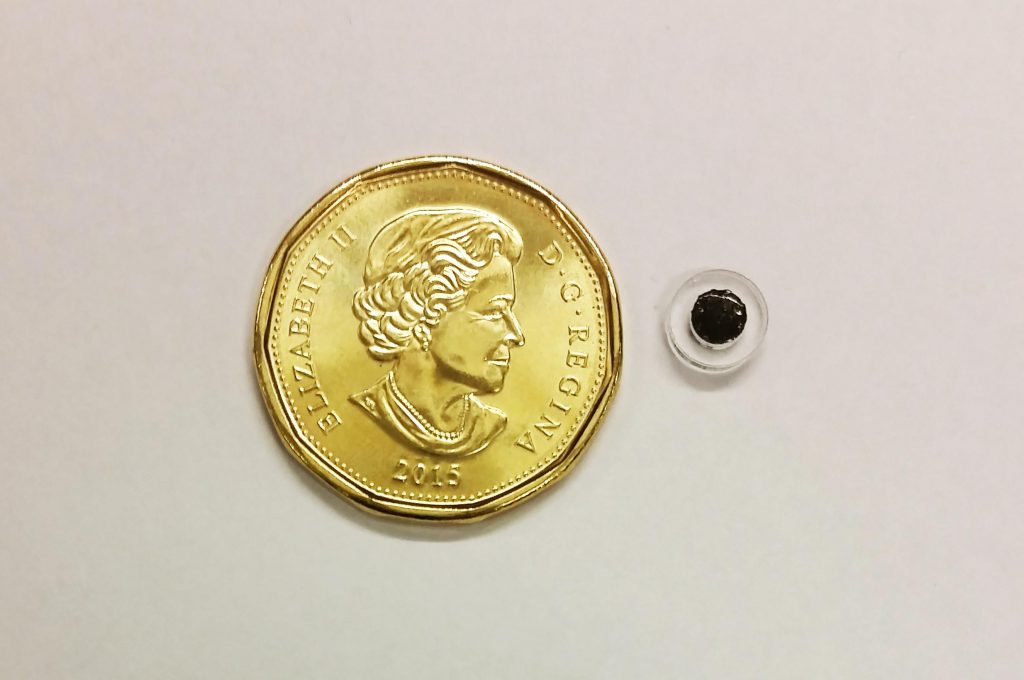

The tiny medical device – just six millimeters in diameter – is composed of a silicone-based sponge impregnated with magnetic carbonyl iron particles. Drugs can be injected into the sponge layer, which is surrounded by a polymer, allowing it to be surgically implanted into the body.

The amount of drug released by the device is controlled by passing a magnet over the site of implantation. The magnet triggers the release of the drug from the spongey interior, which flows into the surrounding tissue through a small opening in the device.

“Drug implants can be safe and effective for treating many conditions, and magnetically controlled implants are particularly interesting because you can adjust the dose after implantation by using different magnet strengths,” said Ali Shademani, a PhD student in the biomedical engineering program at UBC. “Many other implants lack that feature.”

The device could be helpful for patients with diabetes, as the dosage of insulin is crucial to maintaining healthy blood sugar levels. The researchers published more details on the device in the journal, Advanced Functional Materials.

“This device lets you release the actual dose that the patient needs when they need it, and it’s sufficiently easy to use so that patients could administer their own medication one day without having to go to a hospital,” said John K. Jackson, a research scientist in UBC’s faculty of pharmaceutical sciences, and co-author of the study.

In testing the device, the researchers found that it was able to repeatedly deliver the drug every time the magnet was passed over the animal tissue. They also found that the effectiveness of the drug was not diminished despite being stored in the implanted device.

“This could one day be used for administering painkillers, hormones, chemotherapy drugs and other treatments for a wide range of health conditions,” said Mu Chiao, a professor of mechanical engineering at UBC, and senior author of the study. “In the next few years we hope to be able to test it for long-term use and for viability in living models.”

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN