Update (October 22, 2018): Further research has strengthened the hypothesis that Alzheimer’s disease could be linked to herpes virus infection. New studies suggest that 50 percent of all cases of Alzheimer’s could be caused by the herpes virus and that treatment with antiviral medications may reduce the risk of developing dementia.

Originally published on June 25, 2018:

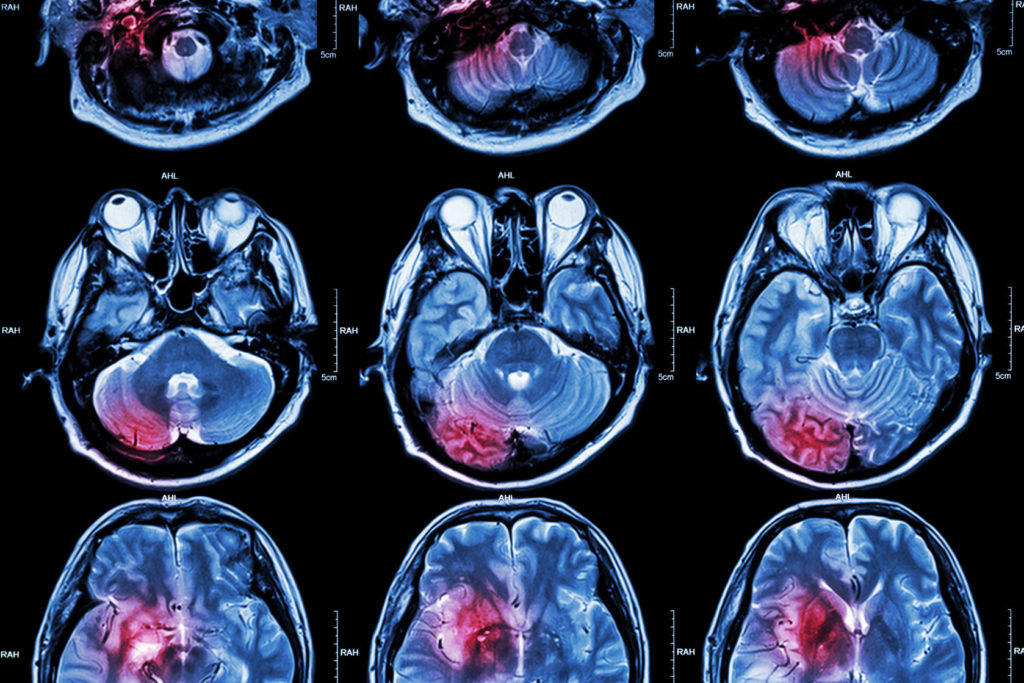

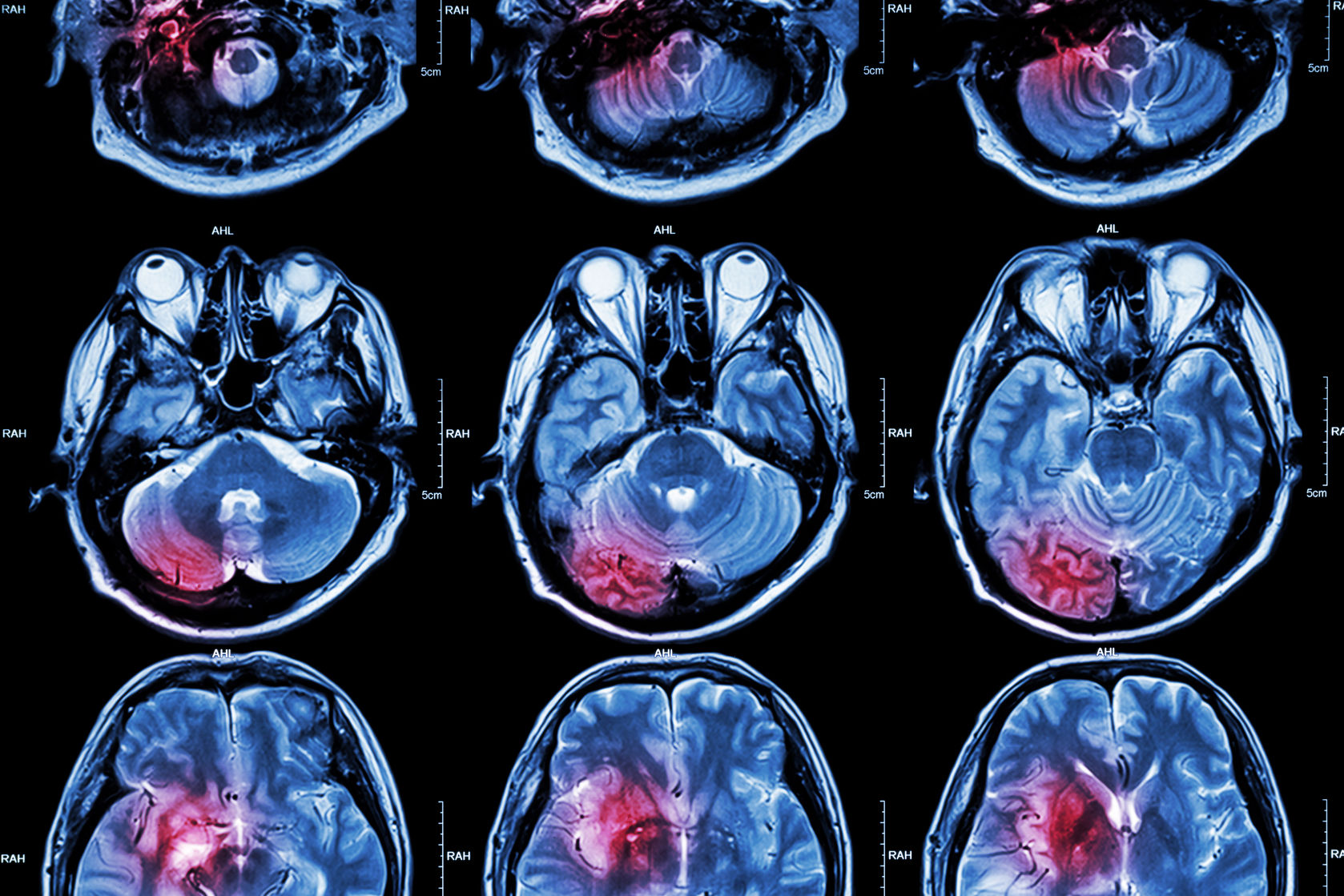

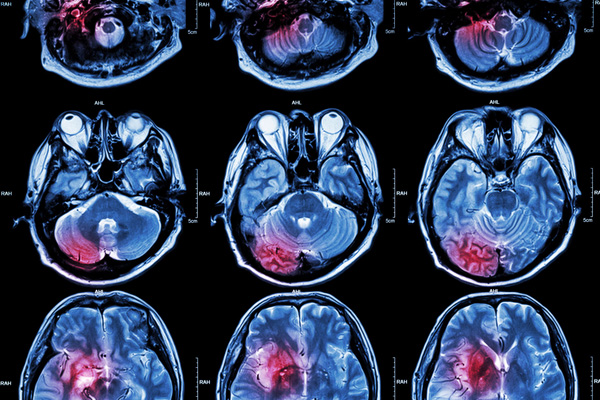

Researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai have found evidence of two different strains of herpes virus in the brains of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease, suggesting the neurodegenerative disorder may have a viral link. While the study – published in the journal Neuron – doesn’t prove causality between herpes virus and Alzheimer’s, it does suggest that the pathogen could accelerate neuronal deterioration through its interactions with brain cells.

“Our hypothesis is that they put gas on the flame,” said study author Joel Dudley, associate professor of genetics and genomic sciences at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai in New York City.

According to reports by NPR, this isn’t the first time that viral infection has been touted as a possible driver behind the development of Alzheimer’s disease. But because the results of the current study appear to, at least in part, support this theory, antiviral drugs or immune system modulators could one day be used to slow the progression of the disease.

“The data are very provocative, but fall short of showing a direct causal role,” said Dr. Richard Hodes, director of the National Institute on Aging. “And if viral infections are playing a part, they are not the sole actor.”

Dudley and his team originally set out to study the genetic differences in brain tissue collected from healthy individuals and those with Alzheimer’s disease in an effort to uncover potential new drug targets. What they found was that brain tissue from individuals with Alzheimer’s contained up to twice as much of two strains of two human herpes viruses, HHV-6 and HHV-7.

“Viruses were the last thing we were looking for,” said Dudley. “When we started analyzing the differences, it just sort of came screaming out at us from the data.”

These two types of herpes virus are commonly found in children, and after often responsible for the development of a skin rash known as roseola. However, the viruses are also neurotrophic, meaning they can infiltrate the cells in the brain and lay dormant for long periods of time.

In order to understand how the herpes viruses might be interacting with neurons and contributing to the advancement of Alzheimer’s, the researchers sought to identify any points of contact. They found that viral genes interacted with key genes known to affect an individual’s risk of developing Alzheimer’s, and in turn, those genes promoted herpes virus infection in the brain.

Dudley and his team postulate that some sort of as-yet-unidentified mechanism in the brain is responsible for triggering viral replication of herpes. Once the virus is reactivated and begins to replicate, the researchers believe it impacts how tau tangles and beta-amyloid plaques begin to accumulate in the brain. The body also seems to mount an immune response against the herpes virus infection, which could also explain the immune activation element of Alzheimer’s.

After decades of late-stage failures in development of new therapies to treat Alzheimer’s, Dudley and his colleagues suggest that a new approach be taken. Perhaps targeting the herpes virus infection itself with antiviral drug therapy, or deactivating the brain’s immune system could be potential new approaches, however neither is without its challenges and risks.

“The more we learn about the disease process and the more targets we can address,” said Hodes, “the greater the probability we are going to slow or prevent the progression of Alzheimer’s disease.”

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN