The advent of personalized medicine has seen oncologists and other clinicians looking for ways to predict a patient’s response to treatment before it is administered. Now, researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania have identified a relationship between the genetic status of tumors and risk of resistance to chemotherapy in patients with a confirmed BRCA1/2 mutation.

Mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes have been implicated in about 5 percent of breast cancer cases and 20 percent of ovarian cancers. According to the National Cancer Institute, over 40,000 individuals will die of breast cancer this year, with 14,000 deaths due to ovarian cancer.

Resistance to cancer treatment is a multifactorial issue, with genetics, the immune system and the tumor microenvironment itself all contributing to the problem. However, the BRCA1/2 mutation’s effect on a patient’s response to treatment had not been characterized.

“Our primary question was not aimed at evaluating resistance to therapy, but we did end up there,” said Dr. Katherine Nathanson, deputy director of the Abramson Cancer Center, and director of Genetics at the Basser Center for BRCA. The team published their findings in the journal, Nature Communications.

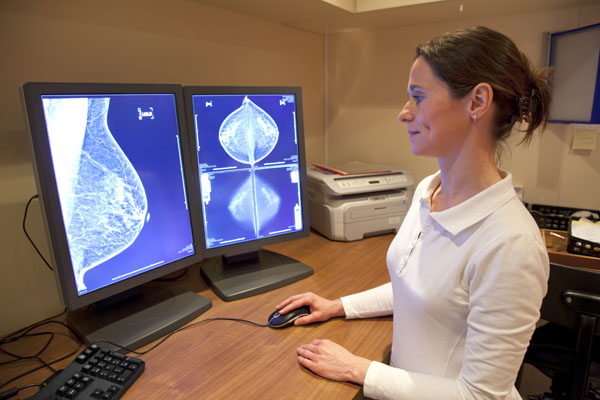

In their study, Nathanson and her colleagues looked at the genetic profiles of 160 breast and ovarian cancer samples taken from patients with germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Specifically, they sought out to quantify how often the non-mutated copy of the BRCA1/2 gene became non-functional – a phenomenon known as loss of heterozygosity (LOH).

Previous research had suggested that all tumors with BRCA1/2 mutations undergo an LOH, however the researchers found that a large percentage of patients in the current study retained a functional second copy of the gene. They also noted both genetic and clinical differences between these LOH-negative tumors, compared to LOH-positive cancers.

Ovarian cancer patients with LOH-negative tumors showed reduced overall survival when treated with platinum chemotherapy, compared to LOH-positive patients. Those with one working copy of the BRCA1/2 gene (LOH-negative) had a median survival of 39 months, while those with two non-functional copies (LOH-positive) survived for 71 months.

Since platinum chemotherapy targets the tumor DNA to destroy the cancer, the researchers believe that LOH-negative cells retain the ability to repair some of this damage, thereby increasing its resistance to treatment. Because the LOH-positive cells contain no functional copies of BRCA1/2, it’s believed that these tumors are more susceptible to DNA damage and cell death induced by the platinum chemotherapy.

“Identifying the LOH status of BRCA1/2 carriers may be useful to predict who might be at risk for primary resistance to DNA-damaging agents such as platinum, which has important implications for treatment of patients with these mutations,” said Dr. Kara N. Maxwell, an instructor of Hematology/Oncology at the Perelman School of Medicine. “We only need to determine the LOH at a specific gene’s location, which is more cost effective than sequencing a patient’s whole genome, for example, and compatible with standard testing.”

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN