Novartis’ Zolgensma (onasemnogene abeparvovec) gene therapy has been making significant strides as of late, including dosing of the first Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) patient with the treatment in the UK last week. In addition, recent data from a Phase I trial has shown ‘remarkable’ long-term results for the gene therapy in children with the disease.

SMA is a rare genetic condition that leads to a loss of motor neurons that results in progressive muscle weakness and wasting, paralysis and, when left untreated in its most severe form, breathing difficulties leading to permanent ventilation or death for most patients by the age of two. Every year, approximately 40 children are born with the most severe form of SMA.

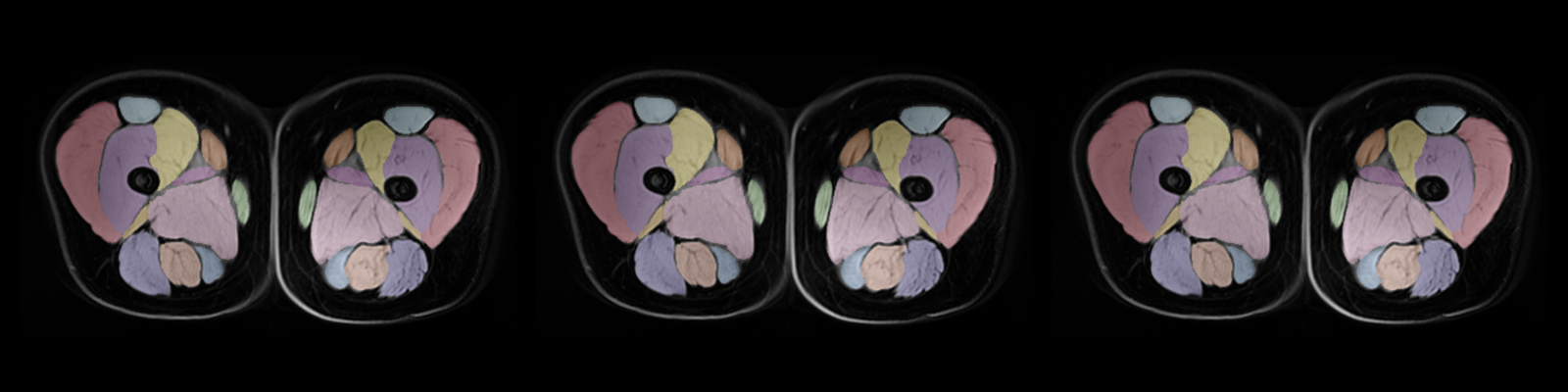

SMA is caused by mutations in the survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene, which along with the SMN2 gene, encode the SMN protein. It forms part of the SMN complex, which is involved in the assembly of snRNPs, the essential components of spliceosomal machinery. The complex is important for the maintenance of motor neurons.

Prior to Zolgensma, treatments could only help manage symptoms and attempt to improve quality of life.

Zolgensma is an adeno-associated virus vector (AAV)-based gene therapy that delivers a functional copy of the SMN1 gene into target motor neurons to replace the mutant copy. It is administered as a one-time IV administration and expression of the SMN protein from the gene improves muscle movement and function, and ultimately survival.

With a price tag of over $2.5 million, Zolgensma is currently the world’s most expensive drug. It was first approved in the US in 2019 to treat children below the age of two with SMA.

Related: Is $2 Million Too Much For FDA-Approved SMA Gene Therapy?

The prevalence of SMA is about one in 10,000 children, and one in 54 people carry the SM1 genetic mutation; two carriers have a 25 percent chance of having a child with SMA.

While SMN1 gene mutations cause the disease, the number of copies of the SMN2 gene modifies the severity and helps determine the type of the condition. There are four main types of SMA — type 0 to IV — with type I being the most common and severe form of the disease. Type I SMA patients present with muscle weakness that is evident at birth or in the first few months of life.

Normally, most functional SMN protein is produced from the SMN1 gene with a small amount produced from the SMN2 gene. While several different types of the SMN protein are produced from the SMN2 gene, only one version is functional while the others are smaller and are rapidly degraded.

While there are typically two copies of the SMN1 gene in a cell, the numbers of SMN2 can vary, with some people having up to eight copies. The presence of multiple copies of the SMN2 gene is typically associated with less severe features of the condition that develop later in life. This is because SMN protein produced by the SMN2 genes can help compensate for the protein deficiency caused by SMN1 gene mutations. People with SMA type 0 usually have one copy of the SMN2 gene in each cell, type I usually have one or two copies, those with type II have three copies, those with type III have three or four copies and those with type IV have four or more copies.

Baby Arthur: First UK Patient

In England, five-month old baby Arthur became the country’s first SMA patient to receive the Zolgensma gene therapy last week through the National Health Service (NHS). In an interview with the BBC, Arthur’s parents say their baby was born six-weeks premature and diagnosed with SMA in April of this year. His parents noticed that he was becoming immobile, “floppy,” had difficulty moving his arms and legs and couldn’t lift his head up (this has already caused some permanent damage), prompting them to take him to the hospital.

In the same piece, the BBC also described UK-based baby Tora’s story who started to exhibit symptoms when she was around three months old — this included difficulty lifting her head when lying on her stomach. At ten months old, Tora had become floppy and did not have any mobility. But after being treated with Zolgensma in the US, Tora is doing well at two and a half years old and can walk with help from her parents, who say the treatment “saved her life” — a life that she has a chance at enjoying now.

In March, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the Scottish Medicines Consortium in Scotland both recommended that the gene therapy be used by the NHS for babies up to the age of 12 months with type I SMA. They also advised use of Zolgensma for infants with SMA type 1 before they develop symptoms.

Due to its high list price, both NICE and the Scottish Medicines Consortium also recommended that the NHS fund the treatment, and came to an agreement with the government health agency over a confidential discount. The discount will allow for dozens of children to be treated with Zolgensma every year.

Zolgensma Gene Therapy: START Trial

Recent data from the ongoing START phase I clinical trial, published in JAMA Neurology, supports the long-term favorable safety profile of Zolgensma in children aged up to six years with type I SMA.

The researchers conducted a long-term follow-up study of the START trial that included patients who completed phase I of the study. The primary objective in the interim analysis was safety and the secondary objective was to evaluate whether developmental milestones reached in the START phase I trial were maintained and whether new milestones were achieved.

Participants included symptomatic infants with SMA type I who had two copies of SMN2 who received prior treatment with low IV doses of Zolgensma in the trial. The analysis included 13 of 15 original participants from the START trial (as two families declined to participate in follow-up).

Prior to baseline, four patients (40 percent) in the treatment group required non-invasive ventilatory support, while six patients (60 percent) did not. This did not change in long-term follow-up. All ten patients in the therapeutic arm retained motor milestones that had been achieved earlier. In addition, two patients achieved a new milestone, “standing with assistance” without the use of the SMN2-targeting oligonucleotide drug Spinraza (nusinersen, Ionis Pharmaceuticals). The study also found that early treatment was better.

The finding that all patients were alive five years after gene therapy, with two participants walking and two standing, “is remarkable,” Jerry R. Mendell, MD, attending neurologist at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Ohio and lead author on the study, said in an interview with Healio Neurology.

Why is Zolgensma So Expensive?

One of the main reasons why Zolgensma has such a hefty price tag is because it has a small market size in the drug manufacturing industry given its limited potential to save lives on a large scale.

Given that SMA is a rare condition, a specialized drug had to be created for it, which required intense research and the right expertise. Moreover, the drug is a one-time dose; “the fewer the cases the higher its price will be,” Dr. Neelu Desai, pediatric neurologist at the P.D. Hinduja Hospital, Mumbai, told FactChecker. Discovering and manufacturing a new drug can cost billions of dollars.

Dr. Desai treated a five-month old with the treatment in Mumbai, India. Due to the exorbitant price of the drug, the patient’s parents launched a crowdfunding campaign to meet much of the cost.

With Arthur being the first to get the therapy last month in the UK, many patient groups and doctors in the country that treat SMA are advocating for it to be added to newborn screening programs.

“We need newborn screening for SMA to be introduced in the UK so that our children have this opportunity for their futures,” charity group SMA UK told the BBC.

“The earlier Zolgensma is given for SMA the better, with pre-symptomatic treatment shown to give the very best possible outcomes. Early diagnosis and treatment is vital.”

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN