If you get badly burned in a fire, you might need to get a skin graft to help replace the dead skin. Similarly, if you lose a limb, you might be able to get a prosthetic to replace it.

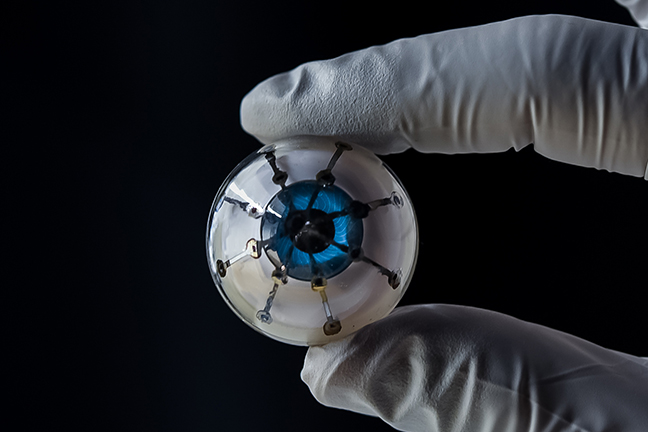

Obviously, not all parts of your body can be replaced. Take the stem cells in your eye. The limbal stem cells, located in the niche (limbus) between the cornea and the sclera (white of the eye), are thought to protect and maintain the cornea. Once lost, these cells cannot be replaced.

In limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD), a damaged limbus leads to a loss of these stem cells and can result in inflammation, irritation, pain and severe vision impairment. Patients with LSCD usually do not respond to standard treatments.

For the first time, researchers transplanted stem cells into patients’ eyes for the treatment of LSCD in a randomized controlled study. The study was published in STEM CELLS Translational Medicine by a collaborative team from the University of Edinburgh and Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service.

“Clinical studies such as these help us to understand how complex new cellular therapies may be able to complement existing medical approaches in restoring function to damaged tissues and organs,” said Dr. Marc Turner, Medical Director of the Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service and Professor of Cellular Therapy at the University of Edinburgh.

The researchers took healthy limbal tissue from deceased donors’ eyes to generate a pool of stem cells for transplantation. Using the same protocol, they generated eye tissue without stem cells as a control. Having a control group ensured that any difference in patient outcome resulted from the addition of stem cells. The 16 patients that participated in the study each received eye drops and immunosuppressive drugs in addition to the transplant.

At 18 months post-operation, the researchers found all patients showed improved vision but the group that received the stem cells showed slightly greater improvement in visual acuity – the sharpness of vision. Some participants who received stem cells also had clearer corneas – a sign that the stem cells could be repopulating the limbus. The researchers speculate that the implanted stem cells could be stimulating endogenous stem cells to proliferate or could be directly signalling the limbus to regenerate.

“The findings from this small study are very promising and show the potential for safe stem cell eye surgery as well as improvements in eye repair,” said lead author and Professor of Clinical Ophthalmology at the University of Edinburgh, Dr. Baljean Dhillon.

As with other new drugs, cell therapies must undergo rigorous safety and efficacy testing before receiving regulatory approval. But they also face some unique challenges that big-box drug manufacturers might not encounter.

“Scaling up” is one of the biggest problems with mass-producing cell therapies. Having the right infrastructure, capital, and an untouchable protocol are often hard to come by. Presently, the authors discuss how complicated ocular cell therapy can be. Since they derived their stem cells from deceased donors, they faced some variability in donor age, time to procurement, transport conditions and tissue processing, which ultimately affected the transplant. This makes it even harder to minimize batch-to-batch variability.

Some so-called “stem cell clinics” have enticed desperate patients to pay thousands of dollars for unproven cell therapies. In a report published by the New England Journal of Medicine, three patients were given stem cell injections derived from their own abdominal fat to treat age-related macular degeneration. Sadly, each patient developed a serious eye disease that required additional treatment.

Before stem cell therapy for the treatment of LSCD becomes available to patients, the researchers must conduct a larger clinical trial. They plan to launch a phase III study involving more patients to further corroborate their data.

In parallel, they are interested in uncovering the underlying mechanism driving these findings.

“Our next steps are to better understand how stem cells could promote tissue repair for diseases that are extremely hard to treat and if, and how, they could help to restore vision,” said Dr. Dhillon.

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN