New research published in the journal Current Biology challenges the long-standing belief that tau protein – infamous for its role in neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease – does not stabilize microtubes within neurons. The findings of the study suggest that tau actually supports microtubule growth and their ability to retain their dynamic nature.

According to the researchers from Drexel University College of Medicine who conducted the investigation, for cognitive function to be normal, microtubules in the brain cells must have both their stable and dynamic regions. This means that tau still plays an important role in this process, however it’s not the same role as previously thought.

“We think the reason why the brain has so much tau is to ensure that there is always a robust dynamic component to the microtubules,” said Dr. Liang Oscar Qiang, the study’s lead author and a research assistant professor in the College of Medicine. “Otherwise, without tau, too much of the microtubule mass of the brain would be stable.”

Qiang and his colleagues say that their findings suggest that drugs designed to stabilize microtubules – a few of which are currently being tested in clinical trials – may be ineffective at treating neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s. Since drug development in this disease area already has a high attrition rate, the suggestion that these microtubule-stabilizing drugs may not work could be devastating for pharmaceutical companies developing the compounds and the patients testing them.

“The popular theory suggests that patients with neurodegenerative diseases are losing microtubules because they are becoming less stable. What our study suggests is that, with the depletion of tau, patients are in fact losing the dynamic regions of microtubule,” said Dr. Peter Baas, a professor in the Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy at Drexel College of Medicine and the study’s principal investigator. “So, by treating neurodegenerative diseases with microtubule-stabilizing drugs, the potential exists for making matters worse rather than better.”

RELATED: Alzheimer’s Disease Associated with Strains of Herpes Virus

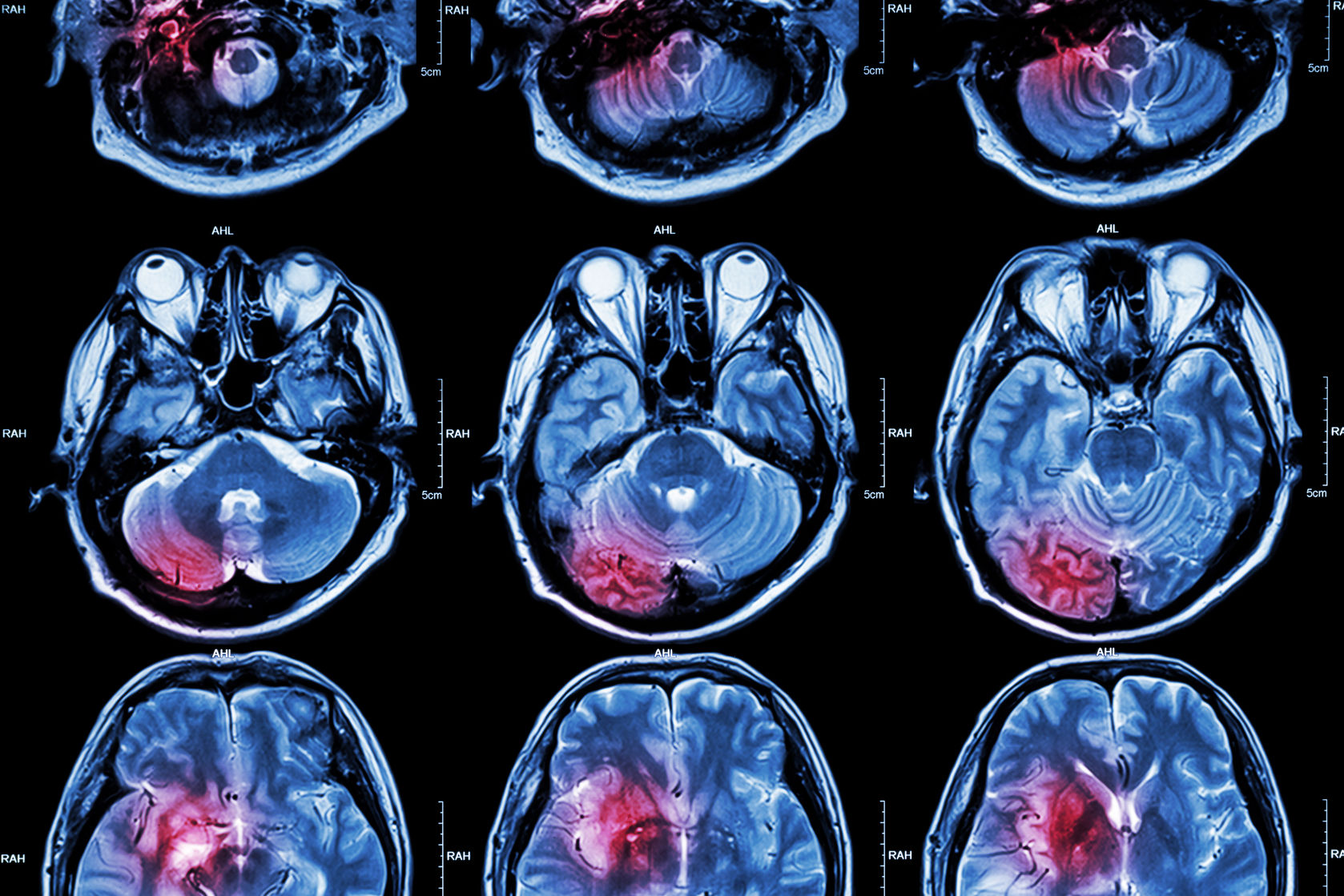

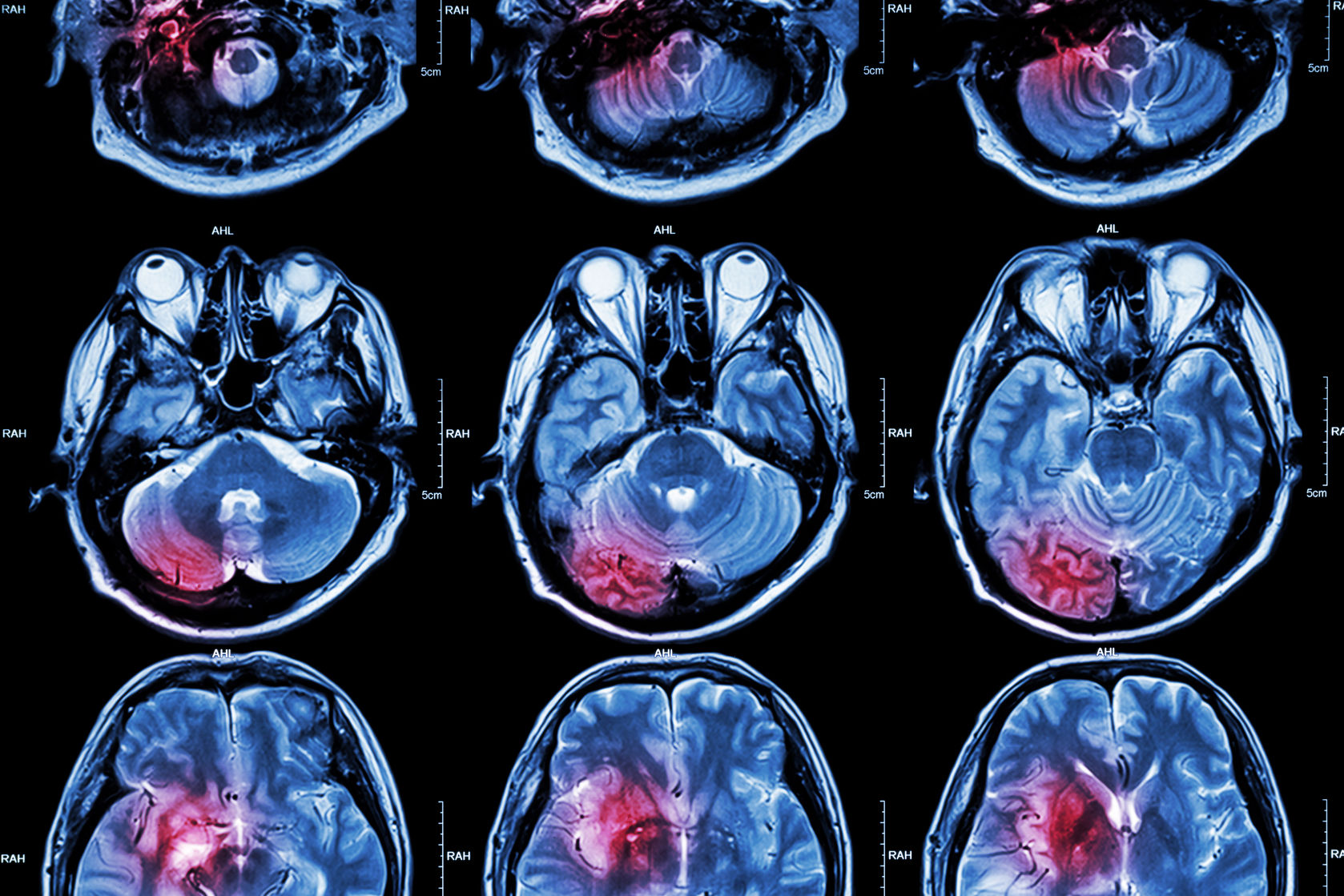

Microtubules are part of the cell’s cytoskeleton which supports the cell and facilitates the movement of organelles throughout the cytoplasm. While tau normally plays a supportive role for these microtubules, in the brain of an Alzheimer’s patient, tau accumulates and forms neurofibrillary tubules which interfere with nutrient delivery to neurons and contributes to cell death.

While the purported role of tau in stabilizing microtubules has been well-documented and widely-accepted in the research community, a paper published two decades ago which challenged this belief prompted the researchers on the current study to investigate the protein. Using cultured rat neurons that had been depleted of tau, the research team measured microtubule levels in the neurons’ axons over a four-day period.

Qiang and his colleagues found that the number of microtubules in the axon was depleted because they lost their dynamic regions, as opposed to the loss being due to destabilization. The researchers noted that the microtubules that remained in the axon appeared to be more stable, suggesting the fundamental role of tau could be quite different than previously thought.

“We found that tau does not stabilize the neuron’s microtubules. The real work of tau is to protect the dynamic regions of microtubules from being stabilized and also to allow them to lengthen,” said Baas.

They also found MAP6, a protein also implicated in microtubule stabilization, covers more of the length of the microtubules in the absence of tau, potentially offering an explanation for why these cytoskeletal components appeared to become more stable without tau protein. The researchers plan to repeat their finding in an adult rodent brain and attempt a rescue experiment to recover the missing dynamic regions of the microtubules in the hope that this approach may reverse neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s patients.

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN