In 2002, a 16-year-old patient developed anemia following a liver transplant to treat cryptogenic cirrhosis. He was prescribed Epogen – a drug designed to stimulate production of red blood cells – which was filled by a mail-order pharmacy run by CVS.

Despite weekly injections with the drug, the patient was unresponsive and fatigued. While this case could easily be explained as an ineffective treatment for this patient, the truth was much more sinister. Two months after starting treatment with Epogen, Amgen released a statement saying that counterfeit vials of the drug had been identified, which were uplabelled to 20 times their actual strength.

Drug counterfeiting is a major threat to public health across the world. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), less than one percent of medicines sold in developed countries – like the US, Canada and the UK – are counterfeit. However, this number rises to between 10 and 30 percent in developing countries in parts of Africa, Asia and Latin America. The WHO originally released these figures in 2006, so current drug counterfeiting estimates could be even higher.

Online Pharmacies

The rise of e-commerce has been a major contributor to the drug counterfeiting trade. Consumers are now able to buy an assortment of medications through online pharmacies, which may or may not be reputable. A recent study conducted by researchers at Imperial College London, found that 45 percent of online pharmacies in the UK dispense antibiotics to patients without a prescription.

What’s more, many online pharmacies serving the US claim to be located in Canada, however under further inspection their operation is often found to be run out of India or China. According to the WHO, medicines purchased from these unverified pharmacies are found to be counterfeit over 50 percent of the time.

Nearly ten years ago, the primary target for drug counterfeiters were lifestyle drugs, such as Viagra, where deep discounts offered on counterfeit versions of popular drugs would almost guarantee big profits. In this case, counterfeit versions of the erectile dysfunction drug would often contain a small amount of the active ingredient, due to the fact that the measurable effects of this drug are so obvious. But in many cases, counterfeit drugs contain no therapeutic ingredient, and can even be laced with dangerous compounds.

Now, all drugs are vulnerable to counterfeiting. Commonly-used and lifesaving medications, including insulin, cancer drugs and cardiovascular disease drugs have all fallen victim to phony manufacturers.

The most pressing danger of counterfeit drugs is, of course, to consumer health. The International Institute of Research Against Counterfeit Medicines (IRACM) publishes a quarterly news report detailing the latest news in fake medicines, worldwide. Between July and September of 2016, IRACM reported that 145 deaths were linked to counterfeit opioid painkillers alone.

Pharmaceutical Supply Chain

In addition to the significant threat public health, counterfeit drugs can result in lost sales and cause damage to the legitimate pharmaceutical company’s brand. Drug trafficking of counterfeit pharmaceuticals is estimated to cost the industry over €10 billion on an annual basis, according to IRACM.

So how can these counterfeit medicines avoid detection in such a highly-regulated and highly-scrutinized industry? The Achilles heel of the pharmaceutical industry lies in the supply chain; almost 40 percent of the drugs that supply the US market are manufactured overseas, with 80 percent of the active pharmaceutical ingredients themselves being imported from suppliers in over 150 different countries.

What’s more, this supply chain is incredibly complex, with some drugs passing through 10 or more points of contact before reaching the patient. All stages of drug manufacturing and supply are vulnerable to drug counterfeiters, from suppliers of raw ingredients for the drug and storage, to transportation and distribution.

One of the most commonly exploited periods is in the event of a drug shortage. Access issues disrupt the usual pharmaceutical supply chain, prompting hospitals and consumers to seek other sources for medicines.

The drug supply chain is composed of two types of wholesalers: primary, and secondary. While primary wholesalers liaise directly with pharmaceutical manufacturers – thereby reducing the chances of counterfeiting – secondary wholesalers do not. These secondary wholesalers often deal in medicines in response to market fluctuations; during a shortage, they may be one of the only suppliers of a medicine.

Real-World Instances of Drug Counterfeiting

In late 2011, the FDA identified 19 US medical practices that were believed to have purchased unapproved medications from foreign sources. An injectable cancer drug, known as Avastin (bevacizumab), was among these medications, and laboratory tests confirmed that the drug contained no active ingredient.

The monoclonal antibody is approved to treat a number of different types of cancer, including colorectal cancer, lung cancer, and glioblastoma. Hundreds of oncology patients were treated with the counterfeit Avastin before it was uncovered that the drug had been tampered with.

Widely-used blood thinner, heparin, was the target of counterfeiters in 2008, when 149 US patients died as a result of using the contaminated drug. The contaminant was identified by federal officials to be an over-sulfated version of chondroitin sulfate, a drug often used to treat arthritis.

According to the FDA, the over-sulfated chondroitin sulfate mimics heparin in lab tests, allowing it to evade detection during quality control analysis. The contaminant was likely added to the raw heparin by the manufacturer as a cheap filler.

Alli (orlistat), an over-the-counter weight loss drug, fell victim to adulterators in 2010. Orlistat is a lipase inhibitor which prevents the body from absorbing fats. The counterfeit version of the drug was found to contain sibutramine, a stimulant drug which has been associated with an increased risk of heart attack and stroke.

In all cases of drug counterfeiting, the product, packaging and label information are designed to look exactly like the original product. Reports of adverse events or suspicious appearances of a drug are often all regulators, like the FDA, have to go on when it comes to identifying counterfeit pharmaceuticals.

Pharmaceutical Serialization

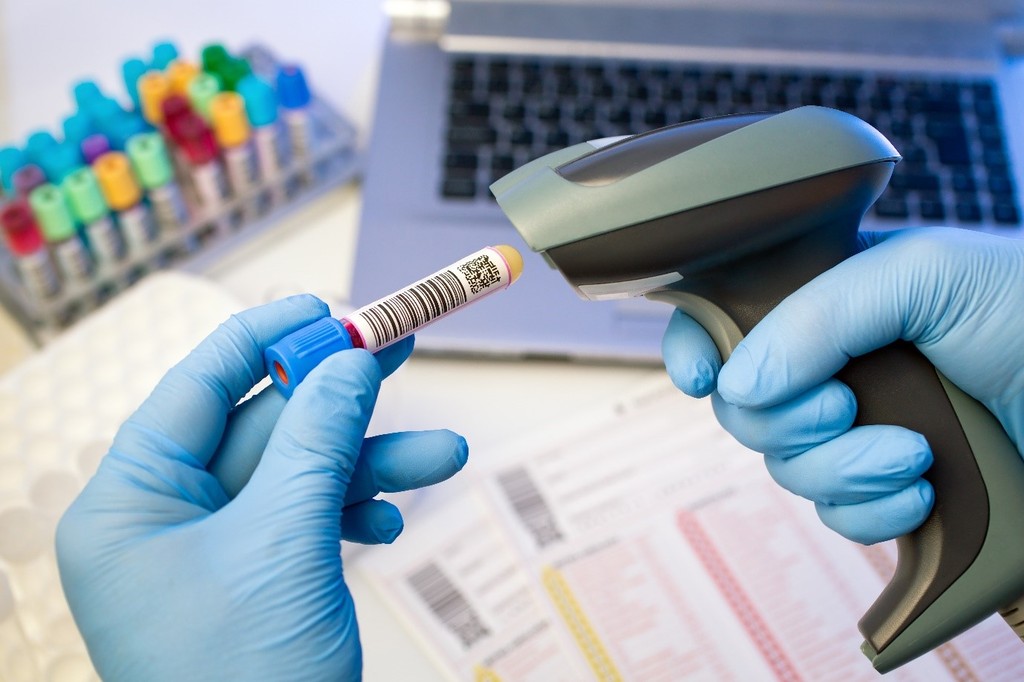

In response to the growing threat posed by drug counterfeiting, international regulators have begun implementing guidelines aimed at increasing control over the pharmaceutical supply chain. In the US, the Drug Quality and Security Act (DSCSA) was signed into law by President Obama in 2013. The law requires pharmaceutical companies to implement a track-and-trace system for prescription drugs to increase transparency of the supply chain, from manufacturer to pharmacy.

Forty countries around the world – including those in Europe, South Korea and Brazil – have established serialization plans aimed at ensuring that all drug products are tagged using a unique 2-D matrix barcode. In the US, all prescription drugs will be required to be serialized at the saleable unit and the case level, starting in November of 2017.

“CordenPharma has decided to start from the beginning and implement an enterprise construction for serialization, because it’s necessary if you want to track everything,” said Mario R. Scigliano, Serialization & Automation Manager, CordenPharma Latina. “There are some other CMOs that aren’t taking this approach because it’s expensive and they’re concerned about managing the integration, especially with Big Pharma and other customers.”

According to Scigliano, the main aim of serialization is to strengthen the pharmaceutical supply chain, and prevent drug counterfeiting. However, he says that track-and-trace technologies also offer other valuable benefits to pharmaceutical manufacturers.

“From a business perspective, serialization technologies can help provide a better understanding of the efficiency of the production line,” said Scigliano. “This level of control is very beneficial to pharmaceutical manufacturers.”

While new serialization requirements could go a long way to preventing dangerous cases of drug counterfeiting, the lack of global track-and-trace standards makes compliance for pharmaceutical manufacturers more difficult. Making progress toward increasing control over the pharmaceutical supply chain is certainly a step in the right direction.

To familiarize yourself with the serialization requirements for existing and emerging markets around the world, and to learn more about how track-and-trace is applied across the supply chain, watch CordenPharma’s webinar, “From Market Compliance to Business Supply: The Necessity For Serialization.”How are you preparing to meet the impending pharmaceutical serialization deadlines? Share your thoughts in the comments section below!

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN