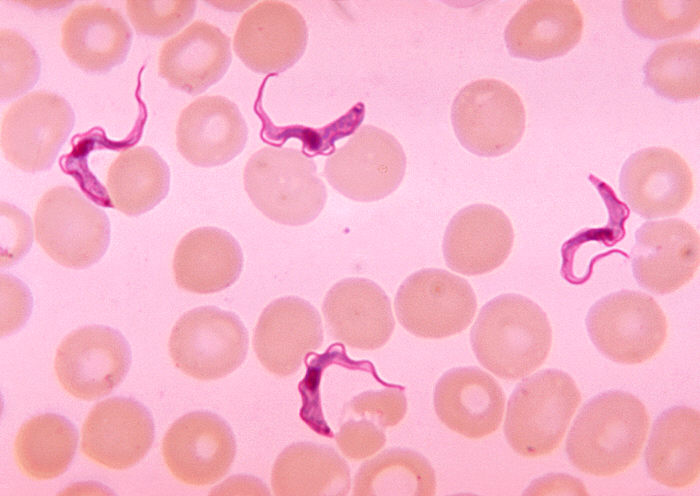

A team of researchers from the University of Glasgow’s Wellcome Trust Centre for Molecular Parasitology and the Institut Pasteur in Paris, have discovered that African Trypanosomiasis – more commonly known as African sleeping sickness – can also be transmitted through the skin. The findings could change the way doctors treat and manage the spread of the illness.

The primary route of transmission of the disease-causing parasite is through the bite of the tsetse fly. If left untreated, the disease can be fatal, which leads to the death of thousands of those in Sub-Saharan Africa every year.

In the current study, the researchers found that a significant number of disease-causing trypanosomes can be found within the skin of infected animals, which are capable of being transferred back to the tsetse fly vector upon contact. Alarmingly, these parasites could be detected even in individuals with no symptoms of the disease, and no detectable level of trypanosomes in the blood.

What’s more, human skin biopsies taken from asymptomatic patients showed the presence of parasites. According to the researchers, the trypanosomes found within the skin could be sufficient to spread the disease among individuals.

“Our results have important implications with regard to the eradication of sleeping sickness,” said Dr. Annette MacLeod, Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Biodiversity Animal Health and Comparative Medicine, University of Glasgow. “Firstly, our findings indicate that current diagnostic methods, which rely on observing parasites in the blood, should be re-evaluated and should include examining the skin for parasites. In terms of treatment, it may also be necessary to develop novel therapeutics capable of targeting sources of infection outside the blood circulation and in the reservoirs underneath the skin.”

According to MacLeod, the new findings make reevaluating current disease control practices a necessity. The World Health Organization (WHO) currently mandates that unless parasites are detected in a patient’s blood, asymptomatic individuals should not be treated. This policy was established on account of the high toxicity and long treatment duration of the current therapy.

“This policy should be reconsidered in light of our compelling evidence that these patients represent a carrier population,” said MacLeod. “This is because their lack of treatment may help maintain disease outbreaks and explain previously thwarted efforts to eliminate this major pathogen.”

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN