According to the researchers, about half of all patients who survive a severe infection with West Nile virus, later experience learning problems, memory loss, difficulty concentrating and irritability. Until now, researchers were unclear as to how the virus caused these symptoms.

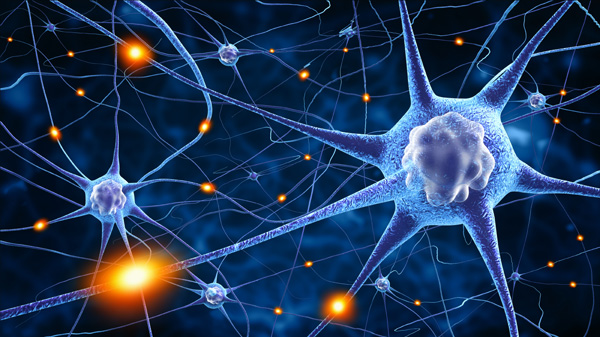

In their study, the researchers – including Dr. Bette K. DeMasters, head of neuropathology at the University of Colorado – found the virus does not have a cytotoxic effect on neurons. Instead, DeMasters and her colleagues identified sources of inflammation associated with the West Nile virus infection, which shorten the synapses responsible for transmitting messages between the neurons.

“What we found in mice, and later confirmed in humans, is that it’s not the death of cells that causes memory loss, it’s the loss of nerve cell connections,” said Dr. Kenneth Tyler, chairman of the department of neurology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, and study co-author. “The viral infection activates microglial cells and complement pathways which are helping to fight the infection but in turn, end up destroying synapses.

In mouse studies, the researchers noticed that West Nile virus-infected animals had more difficulty navigating their way through a maze, compared to healthy control mice. In analyzing the brain tissue collected from these infected mice, DeMasters and her team noted significant damage to the synapses in the brain.

This same phenomenon was found in brain tissue taken from humans who had died as a result of West Nile virus infection. Though relatively rare, West Nile virus is the number one cause of acute viral encephalitis in the US, according to Tyler. Individuals have a one in 100 chance of developing the severe form of the disease, once infected.

“This discovery opens up the opportunity to test therapies and medications on mice as a precursor to humans,” said Tyler. “We already have some drugs that might be good candidates for treating this condition.”

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN