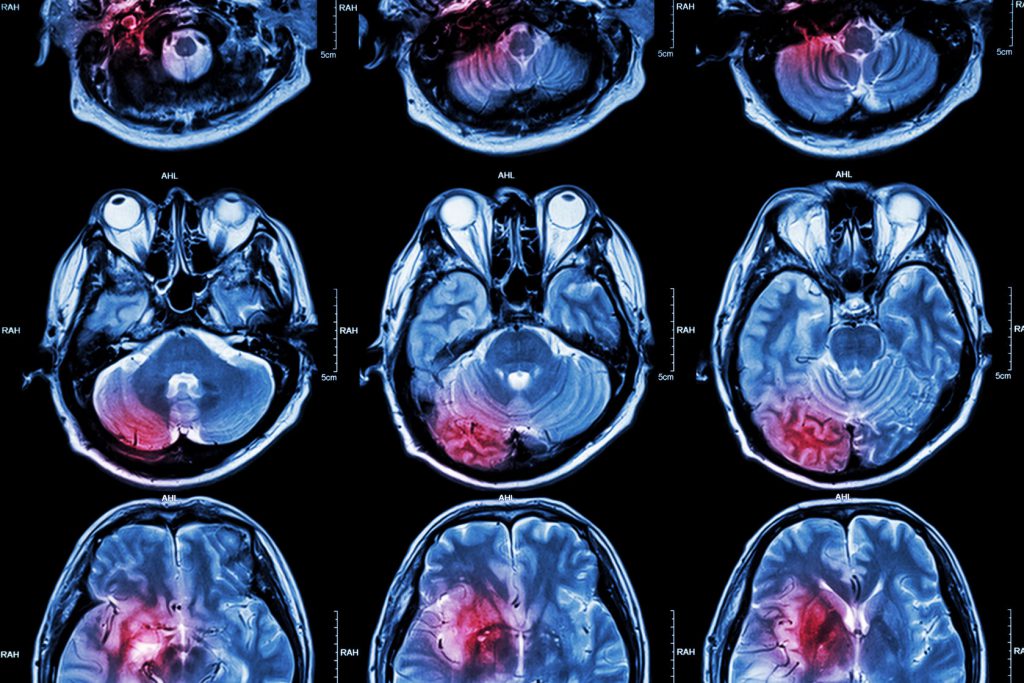

Researchers at University College London (UCL) have identified a blood biomarker which could predict the onset and progression of Huntington’s disease symptoms in patients. While biomarkers for the condition have been previously identified in cerebrospinal fluid, the blood test promises to be easier to obtain and less expensive than earlier methods.

As Huntington’s disease is a genetic disorder, people with a family history of the brain disorder may choose to undergo genetic testing to determine whether they carry the dominant disease-causing mutation. While the results of a genetic test can help patients plan for their future, it does not help doctors predict when a specific patient might start to develop symptoms and how quickly they might progress.

With the availability of a blood-based biomarker, researchers may be able to develop new therapies to help delay the onset of Huntington’s disease. The researchers published their findings in the journal, Lancet Neurology.

“This is the first time a potential blood biomarker has been identified to track Huntington’s disease so strongly,” said senior author, Dr. Edward Wild of the UCL Institute of Neurology. The biomarker is a protein that is released by damaged neurons known as neurofilament light chain (neurofilament).

Wild and his team followed 366 people who participated in an international project called the TRACK-HD study. In measuring levels of neurofilament in blood samples collected from these study participants, the researchers found that the amount of the brain protein predictably increased from the pre-symptomatic to advanced forms of Huntington’s disease.

Carriers of the Huntington’s disease mutation showed levels of neurofilament protein in the blood that were over 2.5 times higher, compared to control participants. What’s more, this protein was predictive of disease onset; the higher the starting level of neurofilament, the more likely a patient was to develop symptoms in the next three years.

“We have been trying to identify blood biomarkers to help track the progression of Huntington’s disease for well over a decade, and this is the best candidate that we have seen so far,” said Wild. “Neurofilament has the potential to serve as a speedometer in Huntington’s disease since a single blood test reflects how quickly the brain is changing.

“That could be very helpful right now as we are testing a new generation of so-called ‘gene silencing’ drugs that we hope will put the brakes on the condition. Measuring neurofilament levels could help us figure out whether those brakes are working.”

Wild and his colleagues say that more research must be done to quality neurofilament as a diagnostic biomarker for Huntington’s disease. Still, they say that the test will help in initiating new clinical trials and developing disease-slowing therapeutics.

“I can see neurofilament becoming a valuable tool to assess neuroprotection in clinical trials so that we can more quickly figure out whether new drugs are doing what we need them to,” said Dr. Robert Pacifici, chief scientific officer of CHDI Foundation, a non-profit research foundation for Huntington’s disease. “As a drug hunter, this is great news.”

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN