Using a fluorescent sensor designed to be activated by misfolded proteins inside the cell, researchers at Penn State University have developed a novel method to test the safety of new drugs. The researchers published the details of this method – which could also be used to detect early signs of protein aggregate diseases, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s – in the journal, Angewandte Chemie International Edition.

While similar methods have been designed to detect cytotoxicity at the point of cell death, the new technique can identify cellular damage much earlier. By studying the cellular damage at the point of protein misfolding and aggregation, researchers can better assess the safety of the drug without having to wait for cell death to occur.

“Drug-induced protein stress in cells is a key factor in determining drug safety,” said senior author Dr. Xin Zhang, assistant professor of chemistry and of biochemistry and molecular biology at Penn State. “Drugs can cause proteins – which are long strings of amino acids that need to be precisely folded to function properly – to misfold and clump together into aggregates that can eventually kill the cell. We set out to develop a system that can detect these aggregates at very early stages and that also uses technology that is affordable and accessible to many laboratories.”

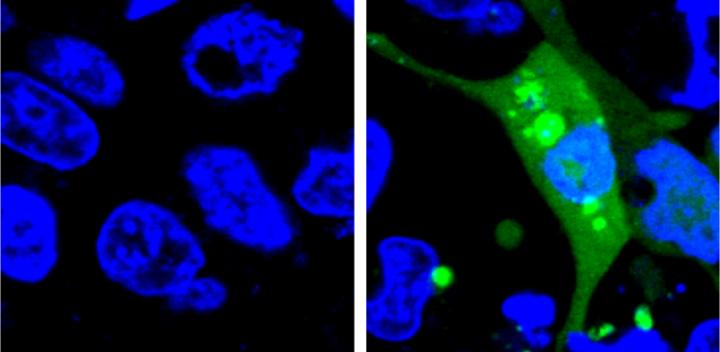

Zhang and colleagues designed an unstable protein – named AgHalo – which is conjugated to a fluorescent dye. As the protein begins to misfold, the fluorescence is triggered by protein aggregation, when AgHalo is buried in the centermost, hydrophobic region of the compound.

Unlike previous cell death detection systems, this novel system only fluoresces when proteins begin to aggregate. Formerly, these techniques would always cause a low level of fluorescence, with signs of cell stress being signaled by brighter concentrations of fluorescence.

“An additional advantage of our system is that the level of fluorescence is correlated to the amount of protein aggregation in the cell, so we can quantify the level of stress,” said first author Dr. Yu Liu, a postdoctoral researcher at Penn State. “Also, because our method measures the level of fluorescence, rather than having to identify the fluorescence under a microscope, it can be done using more accessible technology, like plate readers, and it is much more high-throughput.”

To test their system, the researchers exposed cells to five different cancer drugs which are in use today. Previous drug safety tests indicated that these compounds had no significant effect on cell death. However, using the AgHalo sensor, all five of the drugs showed detectible levels of protein aggregation indicating cellular stress.

“Because we tested the anti-cancer drugs at much higher doses than typically used for treatment, our results do not necessarily call into question the continued use of these drugs,” said Liu. “However, because protein stress from long-term treatments could have lasting effects, evaluating drugs with our new sensor will help in the development of safer drugs.”

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN