Transposons – genes that are able to extricate themselves from one part of the genome, and insert into another location – could play a role in colon cancer development, according to research performed at the University Of Maryland School Of Medicine in Baltimore. While a surprising number of these so-called “jumping genes” are present in the human genome, little is known about their function.

Transposons were first discovered in maize in the 1940s by geneticist, Barbara McClintock. These transposable elements are responsible for some of the colour variation seen in maize kernels, and McClintock would later go on to win the Nobel Prize for her discovery.

While previous research showed that transposons were active in many types of cancer, this is the first time they have been conclusively linked to development of the disease. The research was published in the journal, Genome Research.

The study authors researched a transposon known as L1, which was previously thought to have no effect. In the last 25 years, however, multiple studies have shown that the transposon is active in disease states, including hemophilia and some cancers.

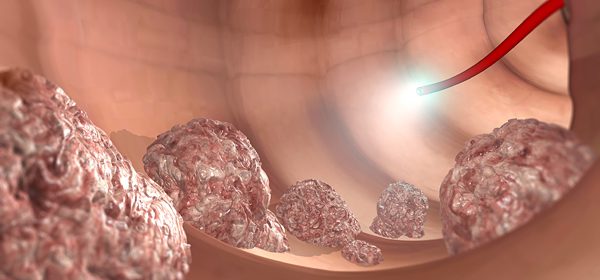

Using new technologies allowing them to track insertion of the L1 transposon, Dr. Scott E. Devine, associate professor of medicine at the University Of Maryland School Of Medicine in Baltimore, and his colleagues found that L1 affects a tumor suppressor gene known as APC. This gene has been shown to be mutated in approximately 85 percent of colorectal cancers.

To figure out how common L1 insertions were among patients with colorectal cancer, the team screened tumor samples taken from ten patients. Evidence of L1 insertions in the APC gene were found in nine of the ten tumor samples, and no evidence of this phenomenon was seen in healthy tissue.

According to the researchers, just one L1 insertion is sufficient to inactivate the APC tumor suppressor gene, allowing tumors to grow unchecked. This L1 insertion also pairs up with a mutation in a patient’s second copy of the APC gene, effectively silencing the gene’s role in preventing cancer.

“This is really a new way to understand how tumors grow,” said Devine. “We think it could explain a lot about the mutation process that underlies at least some cancers.”

As some of the patients tested had a familial history of cancer, Devine suggests that some groups could be more susceptible to cancers resulting from L1 insertions. Interestingly, as over half of our genome is made up of transposons and other mobile DNA elements, it’s likely they also play a crucial role in normal cell functions.

Join or login to leave a comment

JOIN LOGIN